The Last Days of the Incas’ Peru Tour #5 (Cusco)

posted on May 26th, 2008 in Cuzco: Information about the former Inca capital, Incas, Peru, The Last Days of the Incas' Peru Tour

Cusco (3-4 days)

The Arrival of the first Spaniards in Cusco

In 1533, while Francisco Pizarro and his men held the Inca Emperor Atahualpa hostage for a ransom of gold in the north of Peru in Cajamarca, Pizarro sent three of his men—a Basque notary and two former sailors—600 miles southwards to Cusco, a city the Spaniards had only heard about but which they had been assured held vast quantities of gold. Pizarrro’s instructions to his men were to “take possession” of the city for the Spanish crown, and to help expedite the collection of gold and silver for Atahualpa’s ransom. The two sailors and the notary were thus the first Europeans to be carried in royal Inca litters along the spine of the Andes and were also the first Europeans as well to view and enter the Incas’ capital.

Quoting from chapter 5 of The Last Days of the Incas, this is some of what they saw:

“The small procession soon headed south from Cajamarca, climbing the flanks of fantastic mountains, cutting past pale, blue-green glaciers, crossing through Inca cities and villages set besides rivers that sparkled in the sun, then traversing giant gorges on hanging Inca bridges while witnessing vast flocks of llamas and alpacas that seemed to extend for as far as the eye could see. Strangers in a strange land, these were the first Europeans to witness an untouched Andean world never before seen, one with a thriving native civilization in all of its color and scarcely understood complexity. Everything was new—plants, animals, people, villages, mountains, herds, languages, and cities. A trio of Marco Polos adrift in the New World, they were similarly off to seek riches in a distant and fabled city….

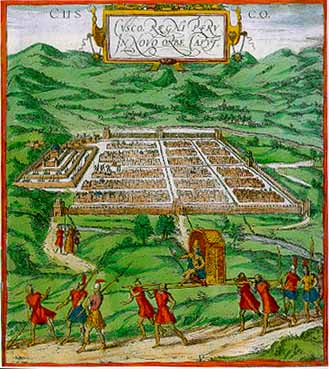

…Like [Hernando] Cortés’ men gaining their first glimpse of Tenochtitlan–the capital of the Aztecs that his fellow Spaniards likened to a city more wondrous than that of Venice–when the three travelers finally arrived in Cuzco, after more than a month of being born ever southwards, they, too, were stunned by what they beheld. Nestled on a hillside that opened into a broad valley at 11,300 feet, the Incas’ mountain capital appeared like some medieval town in the Swiss Alps, with smoke rising from the thatched roofs of its high-gabled houses and with green hillsides and snow-and-ice covered mountains rising in the distance. “This city is the greatest and finest that has ever been seen in this realm or even [elsewhere] in the Indies,” the Spaniards later wrote the King. “And we can assure your Majesty that it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would be very remarkable even in Spain.”

“[It is] full of the palaces of the lords,” wrote one eyewitness, “…The greater part of these houses are made of stone and others have half of the façade of stone…the streets are laid out at right angles. They are very straight and are paved with stones and down the middle runs a gutter for [fresh mountain] water and lined with stone…The plaza is square and the greater part of it is flat and paved with small stones. Around it are four palaces of [native] lords, which are the main ones in the city; they are painted and carved and are made of stone and the best of them is the house of Huayna Capac, a former chief [the father of Atahualpa and Huascar], and the gateway is of red, white, and multi-colored marble and…There are…[also] many other buildings and grandeurs.”

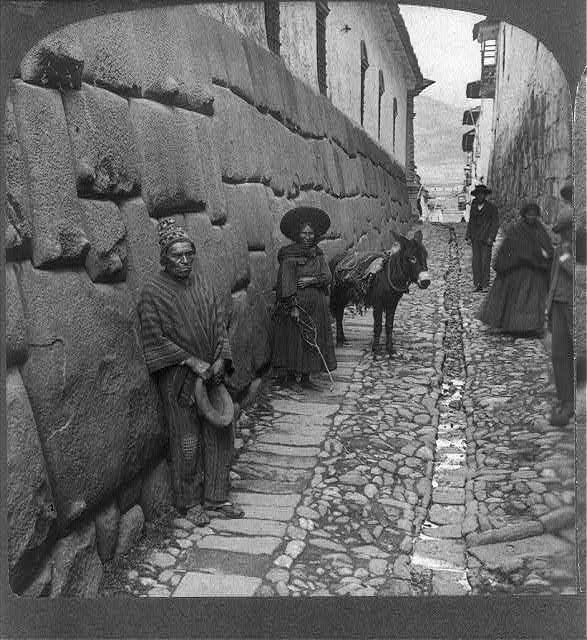

…Everywhere they looked, the Spaniards saw finely constructed stonewalls lining the streets, walls that exhibited the most remarkable craftsmanship the Spaniards had ever seen.

“The most beautiful thing that can be seen among the buildings of that land are these walls,” wrote the chronicler, Pedro Sancho de la Hoz, “because they are of stones so large that no one who sees them would say that they had been placed there by human hands, for they are as large as chunks of mountains….These are not smooth stones but rather are very well fitted together and interlocked with one another.’ “[And they are] so close together and so well-fitted that the point of a pin could not have been inserted into any of the joints.” “The Spaniards who see them say that neither the bridge of Segovia nor any of the structures that Hercules or the Romans made are as worthy of being seen as this.”

The capital of the New World’s greatest empire was a clean, well-engineered, and obviously well organized place. If the hallmark of civilization is the intensification of production of food and other goods and the corresponding increase of population and the stratification of society, then nowhere else was this more apparent than in Cuzco, which in the Incas’ language means “navel.” It was in this very valley—where the four suyus met and formed their epicenter–that the Incas had begun their rise to power. Now the rest of the empire was connected to it via a web-work of umbilical-like roads—roads that, all combined, stretched for more than twenty-five-thousand miles, from the Inca capital to the farthest frontiers.

Here, in the polyglot navel, the ruling emperor lived, and also the lesser lords. It was here, too, that even chiefs from distant provinces had their homes. A sort of “gated” community for the elites, Cuzco was the royal hub of the empire, a city that was purposely meant to display the ostentation of state power. To serve the elites, peasants—the workhorses of the empire and from which all of the nation’s power derived—visited the capital daily and kept it supplied with every conceivable kind of product the elites might require. Everywhere the Spaniards traveled in the city, in fact, they found warehouses stuffed to the ceilings with goods that millions of industrious Inca citizens were constantly churning out, and that were then collected, were tabulated by an army of accountants, and were stored in massive, state-owned warehouses.

As they had been instructed, the three Spaniards “took possession of that city of Cuzco in the name of His Majesty.” The Basque notary, Juan Zárate, dutifully drew up a document that he signed with a flourish and notarized with a seal, as puzzled natives no doubt watched over his shoulder. Neither the natives nor the two illiterate Spanish sailors who had accompanied him could read a word of what he had written.”

(To be continued….)

(Below: street scene in Cusco, 1906)