Was Machu Picchu “Discovered” & Looted 43 Years Before Hiram Bingham’s Arrival? (Part 2)

posted on June 22nd, 2008 in Andes Mountains, Archaeology, Did a German Discover Machu Picchu?, Incas, Machu Picchu, Peru, Recent Discoveries

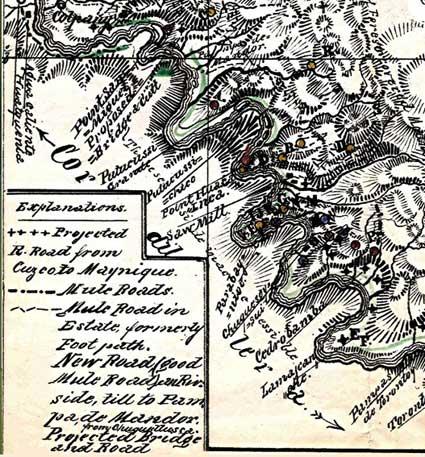

(At left: The American Paolo Greer discovered this map of the Machu Picchu area in Lima’s National Library. It was in an 1877 book by the German geologist, Herman Göhring. The map is dated 1874 and clearly indicates two peaks: “Macchu Picchu” and “Huaina Picchu,” although no accompanying ruins are indicated.)

Machu Picchu Before Bingham (Part 2)

By Paolo Greer

South American Explorer Magazine

Edition 87

June 2008

The Oldest Map of Machu Picchu

In 1989, I was granted an interview with Juan Mejía Baca, the Director of the National Library of Perú. I had spent many weeks in the library and had finally worked up my courage to make a few suggestions to Don Juan about how he might make his archives more accessible.

At the time, I also happened to be searching for a certain book, one written in 1877 by a Herman Göhring, concerning the ill-fated 1873 Baltazar La-Torre attempt to descend the treacherous rivers below Paucartambo.

When I mentioned it to Sr. Mejia Baca, he laughed, saying that he knew of the book, had his library completely searched and was sure it was not there. I said I thought it was and I could find it. The Director politely rolled his eyes.

Within an hour, I located three separate copies, using an obscure index I knew. One of the books still contained Göhring’s map of the expedition, as well as of his own explorations the following year, as a mining engineer in the employ of President Pardo. When the brave La-Torre was killed by thirty-four Native arrows, Göhring escaped. He was nursed back to health by a Señora Yábar in Paucartambo, coincidentally a relative of a friend of mine, Rodolfo Bragagnini. Indeed, it was only for Rodolfo that I sought the lost manuscript.

Even so, Göhring’s work on the Vilcanota sparked an old memory.

More importantly, his map, dated 1874, clearly indicated two peaks, “Machu Picchu” and “Huaina Picchu,” and his 1877 text referred to the “forts of Chuquillusca, Torontoy and Picchu.”

(At left: Göhring’s 1877 report to the Peruvian government, in which he mentions the “forts of Chuquillusca, Torontoy and Picchu,” the latter clearly a reference to Machu Picchu.)

In 1989, the same year that I found the Göhring map, I gave out hundreds of copies to historians, archaeologists and to anyone who feigned an interest. Still, for more than a decade, the oldest known map of Machu Picchu remained remarkably unnoticed.

The only exceptions that I am aware of were Dan Buck, who published the copy I sent him in the South American Explorers Magazine (1993 “Fights of Machu Picchu”) and another I passed on to the Via Láctea newspaper of Cusco in 1999.

In the years that followed, when I wasn’t working pipeline in northern Alaska or squandering my grubstakes prospecting the Inambari headwaters of southeastern Perú, I continued my research on the region of Machu Picchu before Bingham.

I even diligently plied the new phenomenon, the Internet. After two years of early cyber-searching, I learned of a few papers that heirs of an American backer of Berns had put up for sale.

The documents contained Berns’ prospectus and a detailed plan of the Torontoy estate that he had made himself: “I make by hand after a good yellow gumi gusty color. These points more distinct. This is a small work of some hours and will make all falling in the eye at once. Also makes an elegant map. Yours truly. A. R. Berns.”

(At left: A section of Augusto Berns’ handmade map showing his camp, which he marked as “Saw Mill.” Just above it he has written “Point Huaca Inca,” adjacent to Machu Picchu peak. According to Paolo Greer, this map was created before Berns got the Peruvian government’s permission to loot the ruins, so the ruins’ position are unmarked and are described as “inaccessible”).

Berns had his waybill copyrighted, so that no one else could reproduce and publish it. By 1881, he had abandoned his attempts to cut railroad ties and, instead, was promoting the “lost mines of the Inca.”

This pseudo-revelation begs for a side note, on the chance that the tabloids stumble upon this learned magazine. Machu Picchu is made of granite. So is the surrounding terrain for quite some distance. No Inca or Spanish miner took much gold, if any, from granite. To pretend there were rich claims in such barren geology conjures up Mark Twain’s apt description of a gold mine: “A hole in the ground with a liar standing next to it.”

When I found Berns’ “treasure map,” I remembered a similar illustration, the one I had seen years before, in the late 1970s. I compared the two and, though by different hands, realized the first was an inset to Berns’ own drawing.

The sketch I had found earlier was done by Berns’ partner, “Poker Harry” Singer. Singer was an American who had studied chemistry for six years at Gottingen University in Germany and participated in the 1849 California gold rush.

I cannot say for sure what Singer, a real miner, thought of Berns’ shenanigans but the partnership came to an abrupt end.

In 1881, while the two men sat out the Perú-Bolivia-Chile war in Panama, Berns wrote in a letter to his sponsors:

“Here had been shot Mr. Singer about 4 weeks ago as he had drunk together with some Italians, etc., insulting each other and so they shot him.” I had a more difficult time locating the “promotional mining materials” that I had first noted in the 1978 archives directory.

Then, that history was in a University of California library. In the interim, it had been returned to Perú. I traced the line of possession from California back to Lima and eventually found the unique records, uncatalogued, in a large cardboard box, full of bookworms and home to a nest of mice.

I spent a week, sitting between the desks of two librarians, pouring over the rank trove. Regrettably, I was allowed to copy nothing, nor even to take pictures (today, the Peruvian National Library permits reproductions of older books and ephemera to be made with one’s own camera for a charge of two dollars per photo).

I took notes, of course, all the time protesting that this national treasure should be better preserved. In any case, I considered the opportunity just a tantalizing first peek.

A couple years ago, the Biblioteca Nacional of Perú opened its new quarters. Most things probably made the move okay. A box of musty papers, full of wormholes and mouse droppings, apparently did not.

Much has been said and written about the ceramics, shards and mummified bones that Bingham took back to Yale from Machu Picchu. I was delighted to read that those artifacts, at long last, would be returned to their rightful owners, the Peruvian people (update: apparently, Peru’s former first lady’s, Eliane Karp de Toledo’s, February 2008 editorial to the New York Times, may have stopped the exchange).

In any case, I am also concerned that a carton of moldy documents, perhaps the greatest collection of pre-Bingham Machu Picchu information, having already been repatriated, may no longer exist. Much of what I know of Berns’ escapades on the Vilcanota came from my brief preview of the files I examined in that box.

There were twenty-four folders containing the German’s sketches, notes and correspondence. He mentioned a Mr. Oliver, who had been “two years living in those parts.” I found a sample certificate for “The Incas Mines Gold & Silver Mining Company187-.” One folder, alone, had fifty-seven envelopes, addressed to potential patrons.

There was a good drawing of Berns’ camp. I suspect it was of the “Maquina” huts that Bingham saw in ruins, forty-plus years later. It would have been in the same spot where, today, Aguas Calientes thrives and hundreds of thousands of tourists have caught the shuttle for a short ride up the hill to Machu Picchu.

There were seven handwritten drafts of the “Particulars of Torontoy,” Berns’ detailed advertisement to sell his property. From one version to the next, it was telling how he embellished a word here or added another lost mine there.

The box even contained Harry Singer’s original map, in two colors! Although Berns’ own “yellow gumi gusty” plan was nowhere to be found, there were several clear white copies. He hand drew lines on them, from the “Saw Mill” to just downriver, where he hoped the government would build a bridge.

One envelope caught my curiosity as much as anything else. It contained only rusted metal shards. It was without explanation and addressed to a Mr. Mahon.

Why would Berns send heavy pieces of corroded metal to another country? I had an idea, and it had to do with crossing the river.

In 1877, Göhring had dispelled his fellow countryman’s incredible claims of mineral wealth. Still, there was something else, something easier to work and possibly richer! From a different source, I discovered an 1887 booklet explaining Berns’ newer project, a venture he called “Compañia Anónima Limitada Huacas del Inca,” a company having to do with the exploitation of an Inca huaca or “sacred place.” This was no longer about sawing wood for the railroad or mining dubious claims of gold or silver.

Berns was after plunder!

(At left: This booklet, printed in 1877, detailed Augusto Berns’ company and his proposal to loot the “Huacas del Inga,” possibly referring to the ruins of Machu Picchu, among others)

On July 16, 1887, he wrote: “During my stay in those provinces for four years almost continuously, my lengthy investigations and constant expeditions for the purpose, helped by my professional knowledge and casual circumstances, I was able to discover the existence of significant rustic buildings and underground structures that had been closed with stones, some of them carefully carved, which will undoubtedly contain objects of great value, and form part of those treasures of the Incas.”“This company has the participation of the Supreme government and is sponsored by various respectable people of this capital city, as well as several distinguished cuzqueños and antique collectors who will form the directive committee, all persons of the highest honor inspiring the highest confidence and guaranteeing the best results.”

The officers for the enterprise were: President, Augusto R. Berns; Vice President, José M. Macedo; Cashier, Fernando Umlauff; Secretary, Jose Rufino Macedo. Principal members of the company were: Luis Carranza, Luis Esteves, David Matto, Francis L. Crosby, Jacobo Bakus, Arnaldo Hilfiker and Ricardo Palma.

Dr. José Mariano Macedo was a professor of pathology at the San Marcos University in Lima and an officer of the National Medical Academy. He also owned a considerable collection of ancient ceramics. When the war with Chile broke out, Macedo took his collection to Paris and later sold the bulk of the artifacts to a Museum in Berlin.

Berns’ partner, Ricardo Palma, was apparently the well known author and director of National Library of Perú from 1883-1912. Berns often referred to his close cooperation and help from the “Supreme Government.” By that, he meant President Cáceres.

The President probably instructed Palma to support the German’s venture, encouraging the Director to research Machu Picchu, long before Hiram Bingham stumbled upon the ruins. Another piece of the Berns’ affair was brought to light by historian Mariana Mould de Pease.

In her 2003 book, Machu Picchu y el Código de Ética de la Sociedad de Arqueología Americana, Ms. Mould published a letter she had uncovered among the Yale papers of Bingham.

Dated June 16, 1887, it was from the office of the Peruvian President Cáceres to August R. Berns, giving him permission to loot Inca tombs (“construcciones gentilicas”).

Ms. Mould published the letter as an example of the leniency with which Peruvian ruins were “mined” in earlier years. What she did not then know, because the letter gave no clue, was that the “huaca” to be spoiled was the one we now call Machu Picchu.

The government wanted ten percent of the value of any gold, silver or jewels the German found, although it granted the remainder, as well as any objects of copper, clay, wood, stone, and everything else, to Berns without any further obligations, not even custom fees, should he expatriate his treasures.

Berns was required to pay for a Cusco official to make sure the State got its cut, and the authorities would supply police protection, if Berns paid their expenses.

In ‘Inca Land’ Bingham wrote: “With the possible exception of one mining prospector, no one in Cuzco had seen the ruins of Machu Picchu or appreciated their importance. No one had any realization of what an extraordinary place lay on top of the ridge.”

Although Bingham was directed to Machu Picchu, not by Augusto Berns but by Albert Giesecke, the head of the University of Cuzco, Berns was probably the prospector Bingham had heard about, the one who had been to Machu Picchu decades before him.

Who was buried in Grant’s Tomb?

It is accepted that Machu Picchu was built by Pachacuti Yupanqui, the Genghis Khan of the Incas. What is less known is that the famous ruins, perhaps, contained the Inca leader’s tomb.

Pachacuti built the unique Sun Temple or Coricancha, in Cusco. Before his death, he had a similar round temple constructed in Machu Picchu. In addition to being the greatest tourist agent Perú ever had, Bingham also got many things right about Machu Picchu.

He called the cave below the temple, “the Royal Mausoleum.” The mausoleum’s form and masonry are finer than any other Inca burial chamber that exists. Who rated such a crypt, in the city that Pachacuti had built, if not the “World Changer”, himself? The tomb even has its own intihuatana inside it.

My guess is that this “sun hitch,” like the sugarloaf shaped stone placed in the center of the principal plaza of Cusco, more than 500 years ago, was actually a “presidential seal,” not just for the Inca royalty in general, but for one sovereign in particular, Pachacuti Yupanqui.

At the high mark of the ancient ruins, there is the famous intihuatana, the same that was chipped in September 2000 while filming a beer commercial. I also believe that the sugarloaf peaks, Huayna Picchu and Putucusi, were considered natural intihuatanas and probably were the reasons why this location was chosen for “Patallacta” or Machu Picchu.

From the thirty-second chapter of The Narrative of the Incas by Juan de Betanzos: “After he [Pachacuti] was dead, he was taken to a town named Patallacta, where he had ordered some houses built in which his body was to be entombed.”

“Inca Yupanqui ordered that a golden image made to resemble him be placed on top of his tomb. And it was to be worshiped in place of him by the people who went there… He ordered that a statue be made of his fingernails and hair that had been cut in his lifetime. It was made in that town where his body was kept.” The tower above the Royal Mausoleum has a single room, one almost entirely filled by a large hump in the bedrock. It is commonly said that the stone points towards the solstice but it doesn’t. I doubt it points towards anything.

It was the base of Pachacuti’s statue.

The evidence indicates that the pedestal suffered a blistering fire and many fierce blows. Since there no proof that the Spaniards found Machu Picchu, I am fairly sure the vandalism was done to hurriedly break the golden image loose to be used as part of Atahualpa’s ransom to Pizarro.

From Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, History of the Incas (1572): “The Licentiate Polo found the body of Pachacuti in Tococachi, where now is the parish of San Blas of the city of Cuzco, well preserved and guarded. He sent it to Lima by order of the Viceroy of this kingdom, the Marquis of Cañete. The guauqui or idol of this Inca was called Inti Illapa. It was of gold and very large, and was brought to Caxamarca in pieces. The Licentiate Polo found that this guauqui or idol had a house, estate, servants and women.”

Something else that Hiram Bingham noted in Machu Picchu was an “Enigmatic Window.” Certainly, it is rather mysterious. The large opening gives a splendid view of the empty lump of bedrock on top of the Sun Temple, above the Royal Crypt.

There are strange holes bored through its granite periphery, which gave the explorer from Yale the notion to refer to it as the “Snake Window.” He wrote, “The priest of this temple attempted to foretell the future by noticing from which holes the snakes chanced to come out.”

Maybe Bingham had a rustic sense of humor or was simply making do with local hemp for his pipe tobacco but I doubt any snake took a shortcut through that rock wall. The various stone shelves at the window’s base, like the holes, were to support flowers, burnt offerings and other tributes.

The view through the Enigmatic Window seems to have been clearly for that which is no longer there, for the observance and worship of a missing golden sculpture.

Just outside the window are an altar, an extraordinary fountain and a three-sided hut of unusually fine stonework. It was from this vantage that his descendents most likely honored Pachacuti’s effigy.

The Lost Towns of the Metal Miners

Virtually no explorers, national or foreign, discover much on their own.

There were twenty-four families who lived on Berns’ property, one hundred and forty years ago. A few served as his guides. From near his camp, opposite the Vilcanota River from Machu Picchu, Berns climbed up a “well paved road, with massive flights of steps in many parts” that led to two villages, high in the mountains. He called the long abandoned settlements “the towns of the metal workers,” with “ovens,” “smelting houses,” “channels,” “many large baths chiseled out of rock” and “hearths with the doors and windows carefully built up with stone as the Incas left them at the time of the conquest”.

Berns’ company, “Huacas del Inca,” was formed to sack Machu Picchu. These villages, however, were somewhere else, not far away. I have a good idea where, exactly, but I have not been there, yet.

What concerns me is that I believe the huaqueros or looters know the sites well.

The principal town was known as Inkantuyoc or Plateriayoc, “Place of the Silver.” It lies at some distance, beyond the granite of Machu Picchu, where the land morphs into an ore bearing bedrock and placers deposits might well have enriched the valley.

Berns wrote that, after the fall of the Inca Empire, some Portuguese took out great fortunes there. Eventually, the Spaniards caught on how well they were doing but only just before the Native uprisings, preceding the South American War of Independence, caused the miners to run for their lives.

Now, ferocious bulls, descended from those left long ago by the Portuguese, roam “the plains of Plateriayoc.” On occasion, locals still bring some of the animals down to sell their meat. They are wicked beasts and the cracked ribs seem poor compensation for the effort. Berns also wrote of the panthers that preyed upon the wild cattle.

Berns also recorded having seen a ‘large stone statue of an Inca’, one that the locals later secreted away.

“Inca Yupanqui ordered that a golden image… was made in that town where his body was kept…” [Betanzos].

Could the statue that Berns saw have been the model Pachacuti’s sculptors used to make the Inca’s image above the royal crypt?

In 2011, it will be a hundred years since Bingham first climbed the steep jungle slope, to be guided through Machu Picchu by the local boy, Pablito.

Perhaps, in time for the centennial, Plateriayoc will also have been rediscovered, to finally begin the long process of its preservation and careful interpretation.

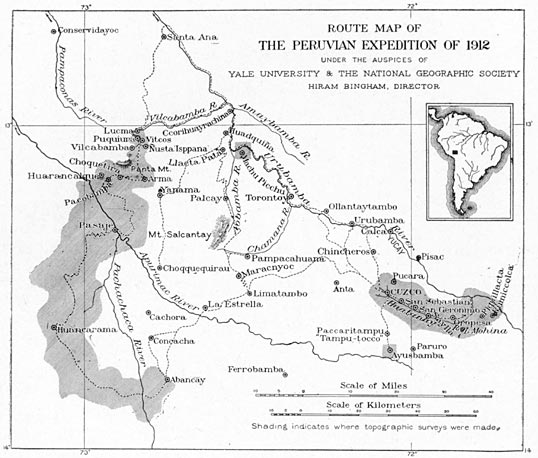

(Below: Hiram Bingham’s Map of his 1912 expedition to Machu Picchu, which shows the locations of Machu Picchu and Torontoy; from “Inca Land: Explorations in the Highlands of Peru,” 1922)

![Herman Göhring’s Informe al Supremo Gobierno del Peru in 1877, which mentions the fort of [Machu] “picchu”](https://www.kimmacquarrie.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/informe-al-supremo-gobierno-del-peru-1877.jpg)