Peru’s Uncontacted Tribes Threatened by Oil Companies and Illegal Loggers

posted on August 16th, 2008 in Amazon Jungle, Environment, Indigenous Rights, Peru, Uncontacted Tribes

The Amazon Rainforest–home to nearly 80% of the world’s uncontacted tribes

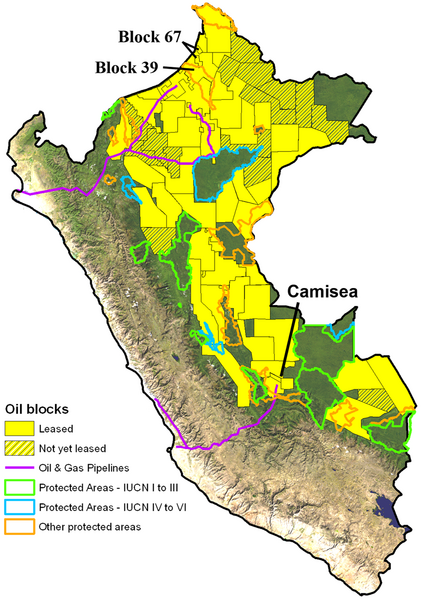

(Note: An estimated 100 uncontacted tribes still exist in the world, with the majority of them inhabiting Brazil (with an estimated 67 uncontacted tribes) and Peru (with 15). Most are located not far from the Peru-Brazil border… in the Amazonian portions of those countries. Meanwhile, more than 180 oil and gas blocks now cover most of the western Amazon, the most species rich area on earth and home to many uncontacted or extremely isolated tribes. Many of these oil and gas concessions currently overlap indigenous territories, that is, land that has either been titled to native groups or else is currently lived upon by isolated tribes. In Peru, 64 oil and gas blocks now cover the Peruvian Amazon; 80% of these have been created very recently, since 2004. In 2006, Peru passed the “Law for the Protection of Isolated Peoples in Voluntary Isolation” (Law 28736). A year later, however, Peru’s President, Alan Garcia, issued a Presidential Decree in October of 2007 stating that reserves for people in “voluntary isolation” (that is, uncontacted or extremely isolated tribes) can be exploited for their natural resources. Many view this decree as a “loophole” designed to allow for the extraction of oil and gas on uncontacted people’s lands. Typically, between 30% and 50% of uncontacted indigenous people often die within a year or two after contact, due to their lack of resistance to germs such as the common cold. The following is a report by Survival International and sent to CERD (the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination)–KM).

Comments Concerning CERD’s Review of Peru, With Specific Reference to Uncontacted Tribes in Peru.

Survival International

June 2, 2008

Survival International is extremely concerned about the situation of Peru’s uncontacted tribes. The Peruvian government is permitting oil and gas exploration in regions inhabited by these tribes, and standing by while other regions inhabited by them are invaded by illegal loggers. The government is failing to uphold the tribes’ rights, and this could lead to the extinction of many of them.

WHO ARE THE UNCONTACTED TRIBES?

Survival estimates there are 15 uncontacted tribes in Peru. They all live in the most remote regions of the Amazon rainforest and have chosen to live in isolation from the outside world.

The majority live in the south-east of Peru, but there are also two tribes in the central rainforest and at least another two in the north. They include the Cacataibos, Isconahua, Matsigenka, Mashco-Piro, Mastanahua, Murunahua (or Chitonahua), Nanti and Yora. The majority belong to two linguistic ‘families’: the Arawak and the Pano.

A recently contacted Yora girl in Peru’s southeastern Amazon

The tribes are nomadic or semi-nomadic, moving across large areas of the forest according to the seasons. They hunt tapir, peccary, deer and monkey, fish, and collect nuts, roots and berries.

It is believed that some of these tribes may have had some form of contact over a hundred years ago during the ‘Rubber Boom’. This ‘Boom’ led to the enslavement, massacre and decimation by disease of thousands of indigenous people. Some of those that survived retreated to the most remote parts of the forest and have remained there to this day.

WHAT THREATS DO THE UNCONTACTED TRIBES FACE?

The threats facing the uncontacted tribes are numerous, but the two most serious are

1) illegal logging and 2) oil and gas exploration.

Oil & Gas Concessions and Protected Areas In Peru

The Peruvian government is permitting companies to explore for oil and gas on uncontacted tribes’ land.

Companies who have already signed contracts with the government and are now working or plan to work in these regions include Perenco, Repsol-YPF, Petrolifera, Petrobras and a consortium led by Pluspetrol.

The uncontacted tribes’ land is also being invaded by illegal loggers. Peru has some of the world’s last commercially-viable mahogany stands and these are, tragically, in the same areas inhabited by the tribes. The loggers also extract cedar.

Logging has led to violent conflict between the loggers and uncontacted tribes, with deaths on both sides. There have also been reports from the Brazilian government’s Indian affairs department (FUNAI) that logging in one region of Peru has forced at least one uncontacted tribe across the Peruvian border into Brazil.

Other threats include road construction and colonists clearing the forest for cultivation.

It should be made clear that Peru’s uncontacted tribes, like uncontacted tribes anywhere, are exceedingly vulnerable to any form of contact because they do not have immunity to outsiders’ diseases. Even something as apparently innocuous as a cold could kill them. Indeed, the history of Amazonia shows that, following first contact, it is very common for more than 50% of a tribe to die. Often that percentage is even higher, and sometimes entire tribes have been wiped out.

Two recent examples demonstrate this. Following initial oil exploration in the Camisea region in Peru’s south-east, the Nahua [Yora] tribe were contacted for the first time. In the ensuing years, more than 50% of the Nahua [Yora] died.

The same tragedy occurred to the Murunahua, also in Peru’s south-east. After being contacted by illegal mahogany loggers in 1996, more than 50% of the Murunahua died too.

GOVERNMENT POLICY AND (IN)ACTION

The government has taken several steps to protect the uncontacted tribes’ rights and land, but these have been completely inadequate.

“Paper Reserves”

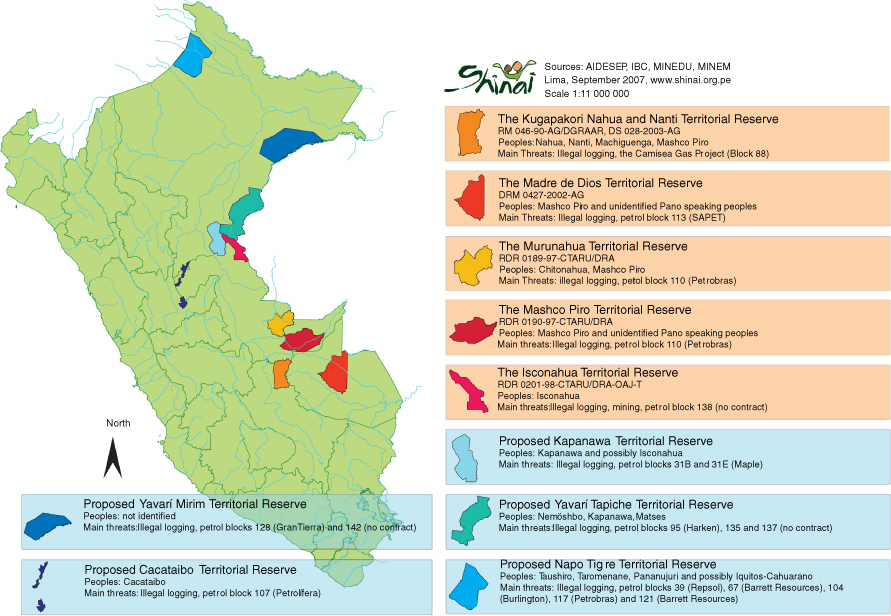

The government has created five Reserves for the uncontacted tribes. However, these Reserves do not recognize the tribes as the owners of this land and all five of them have been invaded by outsiders. They are reserves only in name or, as some people in Peru have put it, ‘paper reserves.’

For example, the Madre de Dios Reserve has been invaded by hundreds of illegal loggers which has led to violent conflict and the deaths of both uncontacted tribesmen and loggers. Much of the Reserve was also included in ‘Lot 113’ for oil and gas exploration until the company, Sapet, after pressure from local indigenous organization FENAMAD, agreed not to enter the Reserve and to modify its boundaries.

Much of the Murunahua Reserve has been included in ‘Lot 110’ where the company Petrobras has a license to explore for oil and gas. This Reserve has also been invaded by hundreds of loggers which has led to violent conflict and deaths. A network of illegal roads has been built to facilitate transporting the wood.

The Mashco-Piro Reserve has been invaded by loggers, particularly on its western side.

The Isconahua Reserve has been invaded by loggers.

The Kugapakori-Nahua-Nanti Reserve, in Peru’s Camisea region, has been included in ‘Lot 88’.

Initial exploration in this area led to the Nahua [Yora] tribe being contacted and the death of more than 50% of their population.

A statement by the chairman of Perupetro, the government body responsible for granting companies the rights to explore for oil and gas in Peru, illustrates how little these Reserves mean in practice. ‘No reserves have been officially created,’ the chairman was quoted as saying in a Peruvian newspaper, ‘so it’s not correct to say that there has been any overlap (between Reserves and oil and gas ‘Lots’).

Proposals for another five Reserves have been made, but to date none of these have been created.

Law

The Peruvian government has passed a law in favour of the uncontacted tribes: Law no. 28736, ‘Law for the Protection of Uncontacted Tribes and those in Initial Contact.’ However, this law does not recognise the tribes as the owners of their land and permits the entry of outsiders into the Reserves if considered a matter of ‘national necessity or national sovereignty.’

Do They Even Exist?

Perhaps most illustrative of the Peruvian government’s attitude and policy to the uncontacted tribes and its failure to recognize and respect their rights are the attempts by various high-ranking members within the Peruvian establishment to deny the tribes’ existence.

Peru’s president, Alan Garcia, wrote an article in one of the Peru’s most widely-read daily newspapers in which he suggested the tribes have been ‘invented’ by environmentalists in order to block oil exploration in the rainforest. ‘In opposition to oil, [environmentalists] have created the figure of an ‘unconnected’ Amazon native; that’s to say, unknown but presumed to exist,’ Garcia wrote in El Comercio, just four weeks after photographs of members of one tribe were published on El Comercio’s front page.

Spokespeople from Perupetro have expressed similar sentiments. During an interview on Peruvian TV, the chairman said, ‘It’s absurd to say there are uncontacted peoples when no one has seen them. So, who are these uncontacted tribes people are talking about?’ In an interview with the US newspaper Washington Post, spokesperson Cecilia Quiroz said, ‘It is like the Loch Ness monster. Everyone seems to have seen or heard about uncontacted peoples, but there is no evidence.’

CONCLUSIONS

The future of Peru’s uncontacted tribes remains desperate. Their lands are being invaded with and without consent of the government and as long as this continues the prospect of contact between them and outsiders remains a very real one. Contact could either lead to violent conflict, or an epidemic in which a large percentage of the tribe is likely to die.

In accordance with international law, the government should immediately recognize the uncontacted tribes as the rightful owners of their land and prohibit any form of natural resource extraction there. It should also prohibit any other form of activity on their land, remove any outsiders who have invaded, and take measures to ensure that no other outsiders can enter in the future.

This is not a question of ‘preserving’ or ‘freezing’ Peru’s uncontacted tribes. Rather, it is a question of giving them the time and space to make their own decisions about how they want to live their lives or what they want to happen on their land, instead of having those decisions made for them by the government, oil and gas companies, or others. One of the things that is clear from all the existing evidence of these tribes is that they do not want contact: on the very rare occasions when they are seen or encountered in the rainforest, they retreat or act aggressively.

We urge the members of CERD to raise these issues with the government of Peru and ask for a concerted effort to recognize the uncontacted tribes’ rights and protect their territory. If this does not happen, Peru’s uncontacted tribes may well be some of the first people to be made extinct in the 21st century.

Below: Proposed and Currently Protected Areas for “Isolated Tribes” in Peru