Ancient Inca Sun Pillars Still Mark June Solstice

posted on July 1st, 2009 in Andes Mountains, Archaeology, Incas, Peru, Recent Discoveries

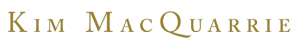

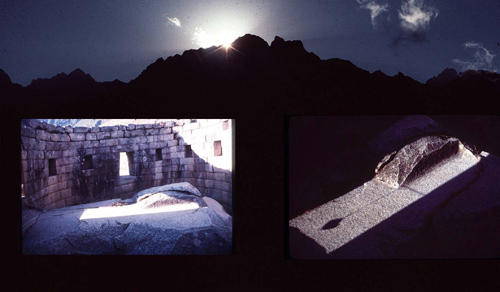

(Above: The Torreón at Machu Picchu is a tower built around a stone that still has a carved groove in it. Once a year, the groove is illuminated as the rising sun shines through one window each June solstice. The window also frames the Pleiades constellation, which was used by the Incas to decide when to plant potatoes. At its height in the early 16th century, the Incas’ 2,500-mile-long empire was littered with celestial observatories, which aided the Incas in the precise sowing and reaping of various crops–KM).

When the Sun Hits the White Granite Boulder, it’s the Solstice

By Nicholas Asheshov

Caretas

On June 21, just over a week from now, the winter solstice, easily the most important day in the ancient Andes, falls due and brilliant rays of sun will be flooding just after dawn through carefully-designed Inca windows onto sharp once-a-year marker stones…

In the old days everyone would be out in the sharp cold dawn at huacas in every valley. I myself will be out too, at a white granite boulder the size of a pick-up truck, in what used to be Huayna Capac’s palazzio at the upper end of Urubamba, beside the cemetery where there is a fine long Inca wall.

I will, like the Incas 500 years ago, be looking up to a couple of stone towers, four metres in height, on a far ridge soaring a thousanad metres above. Beyond these, yet another thousand metres, loom the great snow peaks of the Chicon and Sawasira.

Between the stone towers, on this day a sharp ray of sun will slap precisely onto the white granite boulder, an intihuatanaa, a sacred carved map representing the Urubamba Valley.

I will feel reassured, as people all over the world did and do, that there are solid, precise, predictable events, or as Ecclesiastes puts it,

One generation goes, and another comes; the Earth remains forever. The sun also rises, and the sun goes down and hurries to its place where it rises.

In the Andes it is the mid-year solstice that has always been much the most important simply because it is the dry season and the skies are generally clear of clouds and haze. In December like as not it is pouring, good for the crops but not for astronomers.

I had pointed the sun pillars out some years ago to Kim Malville, Professor of Astronomy at the University of Colorado, and he has since written academic papers on them and on the solstice significance of other sites in the Sacred Valley including Machu Picchu, Llactapata, Ollantaytambo and, in the Cordillera Blanca, Chankillo.

The Urubamba sun pillars can be spotted from anywhere in town and they make a wonderful, steep couple-of-hours walk up to an ancient platform with an outstanding view over a dozen miles of the Valley. Brian Bauer, the Inca-ologist, reported them officially in 1995 as “useful examples of what Inca solar pillars may have looked like”. The reason that Brian says “may” is because there are hardly any left: they were exterminated by the Spaniards as of 1539 as part of the official campaign to destroy the Inca and other cultures.

Kim tells me today: “We’ve established over several June solstices that the Urubamba sun pillars mark the June solstice sunrise very precisely.

“I hope the boulder survives; we had heard that the folks in the cemetery had once thought of breaking it up to make a bridge for their clients.” The boulder is still very much here and elsewhere in the two-hectare main courtyards of the Palace are a couple more. Huayna Capac’s palace is at the centre of Susan Niles’s gripping The Shape of Inca History: Narrative and Architecture in an Andean Empire.

The close relationship of the stars to the Incas and their elaborate astronomy has fascinated the greatest of today’s Andeanist anthropologists, namely Tom Zuidema, of the University of Illinois, and Gary Urton, at Harvard. They have in their different ways combined careful measurements of the ruins, always focusing on the solstice angles and azimuths, and on the stories still told by communeros high in the Andes*.

The Temple of the Sun at Machu Picchu is shut so the best place to watch the solstice is from a point near the quarry from which the great stones of Ollantaytambo were taken. It is one of the most thrilling views easily available in the Andes.

At seven o’clock in the morning of June 21 a sudden shaft of sunlight against a somber early-morning background hits first one, then another and another, walled Inca courts, the size of a small football field. These are part of a pyramid-like set of fine terraces just below the main ruins.

This is Broadway in the Andes.

To get there is an easy hour or so walking from the Inca bridge just above the town along a mule path. All around rise great steep dark slopes, peaks and narrow valleys outlined against translucent mists, whisps of cloud and sharp shafts of sunlight.

At the bottom of a thousand-foot scree is the Rio Vilcanota, including some rapids, pushing on down exactly the same route as it has for at least a thousand years, through ancient maize and potato fields. The Incas lined the sides of this river with stone and they’re still there.

In front rise the snow peaks of the Veronica, ‘Tears of Gold’ in Quechua. In the light of a full moon these great mountains, from this vantage-point, stand out silhouetted against eternity.

On the other side of the river runs the railway track, laid 80 years ago, on its way, along the bottom of the pyramid, from Cusco down to Machu Picchu.

In the little trains people are looking at their electronic watches to see if they are on time.

————————————————————-

*Zuidema, R. T. 1982. Catachillay: The Role of the Pleiades and of the Southern Cross and Centauri in the Calendar of the Incas. Aveni, A.F. & Urton G. (eds.). Ethnoastronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the American Tropics