Atahualpa: The Inca Lord Who Lost an Empire

posted on September 21st, 2014 in Incas, Peru

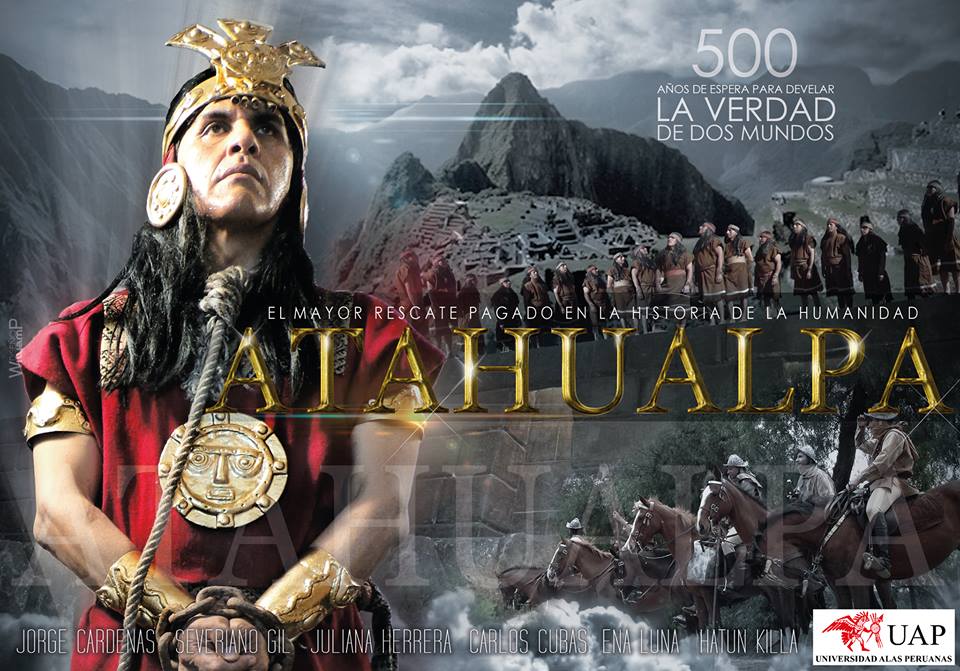

The Inca Emperor, Atahualpa

Atahualpa: Emperor of the Incas

Note: Atahualpa, lord of the Incas, was captured in Nov of 1532 by 168 Spaniards. Atahualpa was captured in the Inca town of Cajamarca, in what is now northern Peru. The following is an extract from The Last Days of the Incas:

“Most Inca accounts state that after [Atahualpa’s father] Huayna Capac‘s death, the latter’s son Huascar was crowned as emperor in Cusco, a thousand miles to the south. Another son, Atahualpa, remained in Quito, meanwhile, which Huayna Capac had made into an ancillary capital during his constant campaigns in what is now Ecuador. Born from different mothers, Atahualpa and Huascar were half-brothers.

Huascar, however, being the son of both Huayna Capac and of Huayna Capac’s principal wife, was a “legitimate” son, while Atahualpa, being the son of one of Huayna Capac’s many concubines, was by definition “illegitimate.” In the labyrinthine political intrigues that occurred during Inca successions, however, this did not necessarily rule out the possibility of Atahualpa ever coming to power. Both were in their mid-twenties at the time of their father’s death, yet had completely opposite temperaments. Atahualpa had been born in Cusco, had lived for many years in the far north with his father, had taken an avid interest in military pursuits, and was known for being extremely severe with anyone who differed with him. Huascar, on the other hand, had been born in a small village to the south of Cusco, had little interest in military affairs, drank to excess, commonly slept with married women, and was known to murder their husbands if they complained. If Atahualpa was the serious type, then Huascar was the party boy. Each, however, bore a sense of entitlement that made him ruthless if even the smallest portion of those entitlements was threatened.

Though Atahualpa and Huascar shared the same father, they belonged to completely different royal descent groups, or panaqas. Atahualpa belonged through his mother to the descent group known as the Hatun ayllu, while Huascar belonged through his mother to the group known as the Qhapaq ayllu. Both of these descent groups were competitive with one another, having struggled for supremacy and power now over several generations. And, as royal successions often provided the spark that unleashed open political warfare, from the moment that Atahualpa did not show up in Cusco for his father’s massive funeral and for his brother’s subsequent coronation, Huascar became suspicious. Huascar’s paranoia–derived no doubt from an Inca history that was richly embroidered with tales of brutal palace coups– became so acute that he is even said to have murdered some of his relatives who had accompanied his father’s corpse to Cusco, having suspected them of plotting an insurrection.

Huascar’s suspicions eventually got the better of him, suspicions that were presumably only accentuated by the inefficiency of the many messages and counter–messages that had to be carried between the two brothers over a thousand miles each way by relay runners. The newly crowned emperor finally decided to wage a military campaign in order to settle the question of succession once and for all. His decision to launch a war was not well thought out however, for it immediately put Huascar at a disadvantage.

Since Huascar’s father, Huayna Capac, had been carrying out extensive military campaigns in the north, his brother Atahualpa now had the advantage of being able to take command of the empire’s most seasoned and battle-hardened troops. The troops were led by the empire’s three finest generals, who immediately pledged their allegiance to Atahualpa. Huascar, by contrast, was forced to assemble an army of native conscripts who had little if any military experience. Where Huascar in the south led a largely untested army, Atahualpa commanded a seasoned imperial force. Nevertheless, Huascar quickly went on the offensive, sending an army north into what is now Ecuador, under the command of Atoq (“the Fox”).

The two Inca armies met on the plains of Mochacaxa, to the south of Quito. There the northern army, supervised by Atahualpa, scored the first victory in what was now a full-fledged civil war. Even in victory, however, Atahualpa’s severity with those who dared challenge him was evident when General Atoq was captured. Atoq was first tortured and eventually executed with darts and arrows. Atahualpa then ordered Atoq’s skull to be fashioned into a gilded drinking cup, which the Spaniards would note that Atahualpa was still using four years later.

With the momentum now on Atahualpa’s side, his generals began a long military advance down the spine of the Andes, gradually pushing Huascar’s forces further and further south. After a long series of victories on the part of Atahualpa’s forces and defeats on the part of Huascar’s, a final climactic engagement was fought outside Cusco during which the Inca emperor himself was captured, as described by the sixteenth-century chronicler Juan de Betanzos:

Huascar was badly wounded and his clothing was ripped to shreds.

Since the wounds were not life-threatening, [Atahualpa’s General] Chal-

cuchima did not allow him to be treated. When daylight came and it was

found that none of Huascar’s men had escaped, Chalcuchima’s troops

enjoyed Huascar’s loot. The tunic Huascar wore was removed and he

was dressed in another from one of his Indians who was dead on the

field. Huascar’s tunic, his gold halberd [axe] and helmet, also gold, with

the shield that had gold trappings, his feathers, and the war insignias he

had were sent to Atahualpa. This was done in Huascar’s presence, [as

Generals] Chalcuchima and Quisquis wanted Atahualpa to have the

honor, as their lord, of treading upon the things and ensigns of enemies

who had been subjected.

Atahualpa’s northern Inca army now marched triumphantly into Cusco. It was led by two of Atahualpa’s finest generals, Quisquis and Chalcuchima, who had successfully directed the four-year-long campaign. One can only imagine what the citizens of Cusco thought, seeing their former emperor stripped of his insignias and royal clothing, wearing the bloodstained clothing of a mere commoner, bound and led down the streets on foot, while Atahualpa’s generals rode majestically in their decorated litters, surrounded by their victorious troops.

The aftermath of the civil war to determine who would inherit the vast Inca Empire–and all the peasants and fertile lands within it-was as predictable as it was brutal. Within a short while, Inca troops rounded up Huascar’s various wives and children and took them to a place called Quicpai, outside Cusco. There the official in charge “ordered that each and everyone learn the charges against him or her. Each and every one was told why they were to die.” As Huascar’s captors forced him to watch, native soldiers methodically began to slaughter his wives and daughters, one by one, leaving them to hang. Soldiers then ripped unborn babies from their mothers’wombs, hanging them by their umbilical cords from their mothers’ legs.

The rest of the lords and ladies who were prisoners were tortured by a type

of torture they call chacnac [whipping], before they were killed,” wrote the

chronicler Betanzos. “After being tormented, they were killed by smashing

their heads to pieces with battle-axes they call chambi, which are used in

battle.

Thus, in one final orgy of bloodletting, Atahualpa’s generals exterminated nearly the entire germ seed of Huascar’s familial line. Huascar was then forced to begin a long journey northward on foot to face the wrath of his brother. The lengthy contest between who would inherit the vast Inca Empire had finally reached its bloody and climactic end.

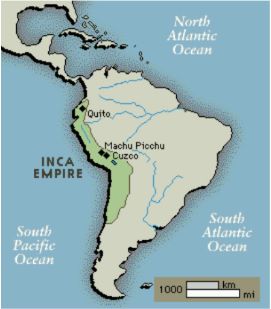

The Inca Empire, circa 1532 A.D., at the time of Atahualpa

Atahualpa, meanwhile, had traveled southward from Quito to the city of Cajamarca, located in what is now northern Peru, some six hundred miles to the north of Cusco. There he waited for word of the outcome of his generals’ attack on the capital. Even via the Incas’ state-of-the-art messenger system, in which messages were carried by relay runners, or chaskis, news of the final battle and of Huascar’s dramatic capture had to pass between more than three hundred different runners. It would take at least five days to arrive. Only then would Atahualpa receive word that he was now the unchallenged lord of the Inca Empire, emperor of the known civilized world.

With all of his attention concentrated upon the steady, though delayed, stream of successful battle reports sent by his generals, Atahualpa was already busy making preparations for the coronation he envisioned in Cusco, the city of his youth. There, he would preside over the usual massive festivities-the processions, feastings, sacrifices, the debauched drinking and copious urinations-and finally, over the majestic coronation itself. Afterward–as his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had done before him–Atahualpa would no doubt look forward to decades of uninterrupted rule, a monarch whose every action and pronouncement would be considered the divine acts of a god.

Atahualpa Learns of the Arrival of the Spaniards

There was only one minor affair, however, that Atahualpa had yet to attend to before he began his triumphal march southward to claim his empire. Chaski reports of a relatively small band of unusual foreigners, who were now marching into the Andes in his direction, had been reaching him for the last several months. Some of the strangers, he was told, rode giant animals the Incas had no word for as none had ever before been seen. The men grew hair on their faces and had sticks from which issued thunder and clouds of smoke. Although few in number-the royal quipu knots carried by the messengers indicated that there were precisely 168–the foreigners behaved arrogantly and had already tortured and killed some provincial chiefs.Rather than immediately order their extermination, however, Atahualpa decided to allow the strangers to penetrate a short way further into his empire. Protected by his army, Atahualpa was curious to see these strange men and their even stranger beasts for himself.

It was November 1532, the season in which the Andes begins its slow transition into the Southern Hemisphere’s summer. And, as news of the final victory in Cusco continued to race northward on foot along the often lonely and fantastic contours of the Andes, Atahualpa no doubt pondered for a moment this strange intrusion from the west. Who were these people? Why would they dare intrude into an empire where his armies could crush them if he so much as raised his little finger? As Atahualpa listened to the latest report about the bold yet obviously foolish invaders, intermixed with the much more interesting news arriving each day from the south, he lifted up the gilded skull of his former enemy, Atoq, the Fox, took a long cool drink from its rim of gold and bone, then turned his attention to the more pressing matters at hand.”