May 3, 2014

The Telegraph

It sounds like a plot from an Indiana Jones film, but explorers claim to have found ruins hidden deep in a dense and dangerous Amazonian jungle that could solve many of South America’s mysteries – and lead to one of the world’s most sought-after treasures.

(more…)

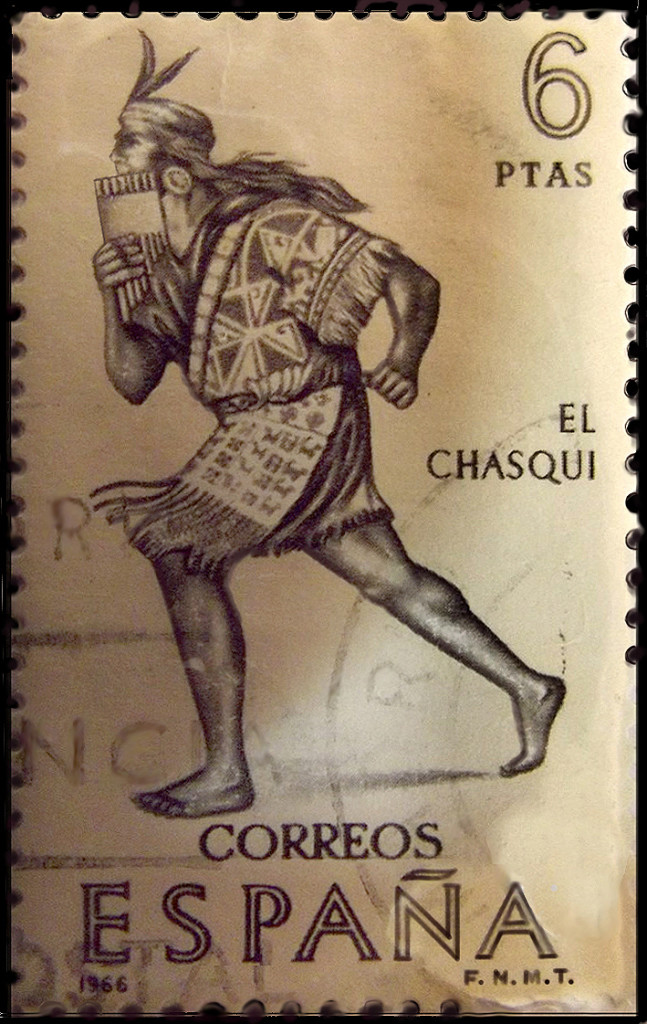

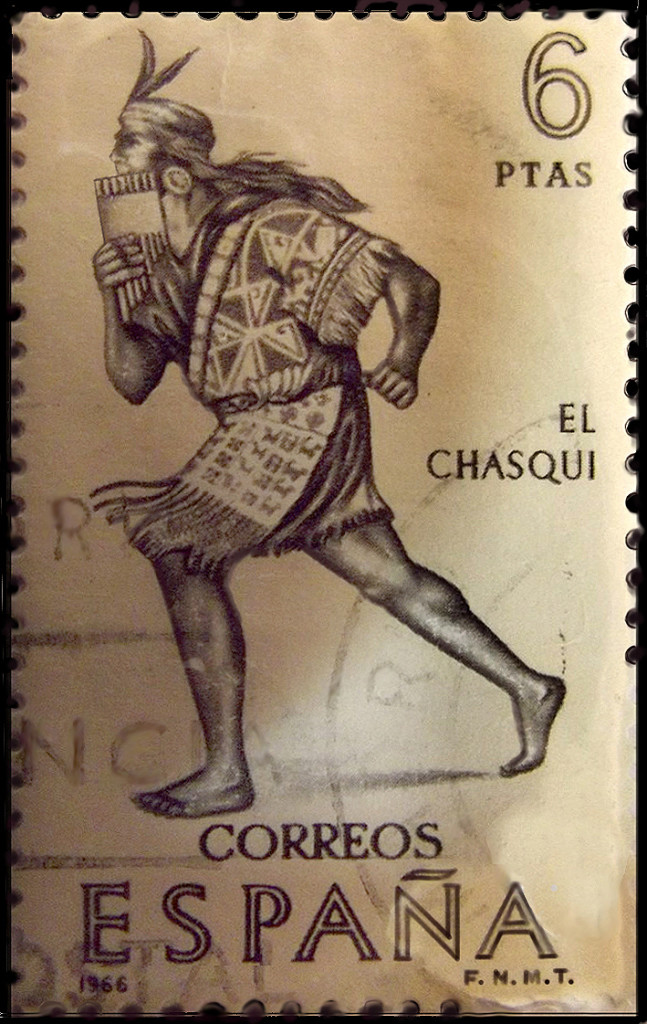

Inka Chasqui runner on Spanish postal stamp

Note: the Incas built one of the greatest roadways in the world, called the Qhapaq Ñan, or “beautiful roadway.” It stretched for more than 2,500 miles in length, from Colombia to mid-Chile, covered more than 26,000 miles of roadway. A tiny stretch of that roadway, which ends at Machu Picchu, is what is now known as the “Inca Trail.” KM

Arequipa: Discovery of Inca Roadway Section

Perú21

March 6, 2014

Translated by Kim MacQuarrie

Early historians noted and were surprised to learn that the Inca [emperor] ate fresh fish, brought from the sea, to Cusco. How did it arrive, they wondered? Now the mystery has been solved with the discovery of about 22 kilometers of Inca roadway, located in the coastal area of the province of Caravelí in the Arequipa region. All indications are that [relay] runners used this route to fulfill that role.

The Kontisuyo Qhapac Nan route was about 400 kilometers long. That stretch links Cusco with the Atiquipa district in the province of Caravelí (Arequipa). And that roadway is currently more relevant than ever, said tourism specialist Rolly Valdivia to our Perú21 correspondent in Arequipa.

“Some sections are thousands of years old as Arequipa continued to play its role in integrating diverse village. Many of these still have no roads,” he stressed.

The design of Qhapac Nan, linking a total of six countries in Latin America, allowed the articulation of a great Tahuantinsuyo [Inca Empire] with transverse and longitudinal paths, where products from the coast, highlands and jungle were transported.

Part of that roadway is the 22 miles of a new section of roadway linking the towns of Chala and Acari, which was discovered by a technical group from the Qhapac Nan Project, of the Ministry of Culture.

This section crosses desert areas and coastal hills , between kilometers 591 and 625 of the South Pan American Highway, in the districts of Chala and Atiquipa.

The Qhapac Nan research coordinator, Guido Casaverde, said preliminary investigations indicate that this stretch of roadway came from the north from the Inca administrative center of Tambo Viejo (Acari) and south to the site of the Tambo (house), connecting the archaeological sites of La Caleta, La Quebrada de Vaca (Puerto Inca) , Quebrada Mocha and Tanaca.

Note:

The Qhapac Nan Project is currently working on having the [remaining] Inca highway designated as a World Heritage Site. During that effort, the project has discovered several new routes.

Date:

Its construction would have occurred in the Late Horizon period, during which the Incas achieved the maximum expansion of their empire.

Excerpt from the Spanish historian, Bernabe Cobo (1582-1657), from History of the Inca Empire:

“The Incas also used the [chaski] runner and messengers when they felt like having something especially delicious that needed to be brought from far away; if, while he was in Cuzco, the Inca [emperor] felt a desire for some fresh fish from the sea, his order was acted upon with such speed that, although that city is over seventy leagues from the sea, the fish was brought to him very fresh in less than two days…the post service of the chasques was held to be one of the great accomplishments of the Inca kings….”

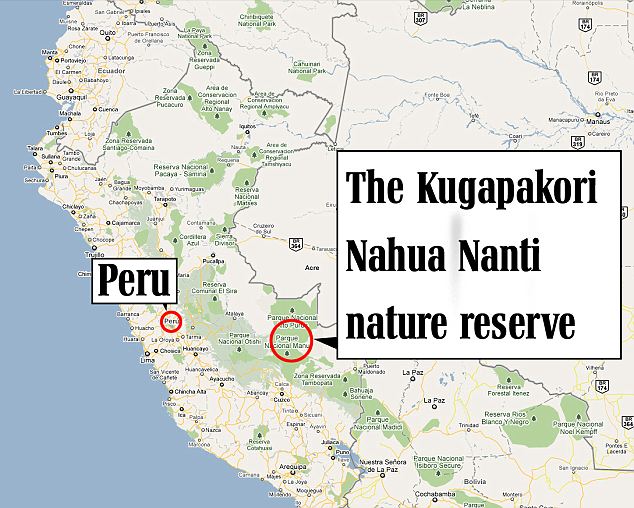

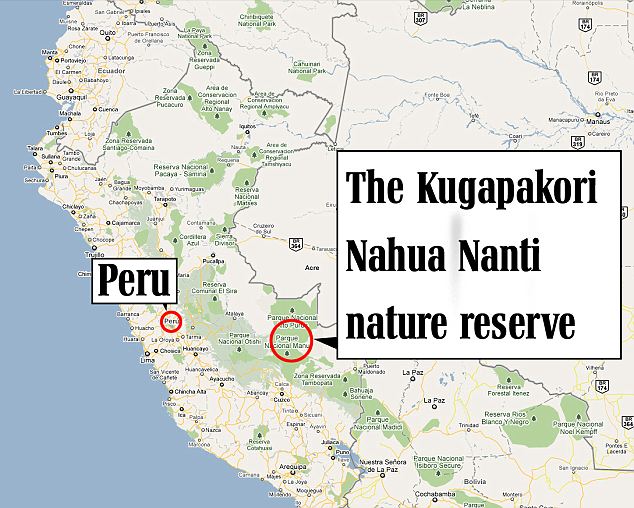

The Kugapakori Nahua Nanti Reserve on the border of Manu National Park, Peru

(Note: the author of this blog lived in this area of Peru with the recently contacted Nahua (Yora) in the late 1980s. The uncontacted Nahua’s land was originally invaded in the early 1980s by Royal Dutch Shell Oil, which detonated explosive charges in their territory. The invasion ultimately led to the Nahua’s contact with the outside world. Roughly 30% of the Nahua population died within two years of the contact, due to an epidemic of whooping cough, for which they had no natural defense.The Peruvian government created the Nahua-Kugapakori Territorial Reserve in 1990 to protect the territorial rights of the Nahua, Nanti (uncontacted Machiguenga) and other uncontacted or recently-contacted peoples living in the area. The reserve also serves as a buffer to Peru’s enormous Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, one of the most biologically diverse areas in the world. Now, thirty years after their first contact, the Nahua and other groups of isolated indigenous peoples are once again under assault, this time by a new group of oil companies, facilitated by the Peruvian government–KM).

January 27, 2014

Peru Approves Gas Project, Spells Disaster for Uncontacted Tribes

Survival International

Uncontacted Nanti could be decimated by plans to detonate thousands of explosive charges and allow hundreds of workers to flood onto their land.

Peru has approved the highly controversial expansion of the Camisea gas project onto the land of uncontacted Amazon tribes – despite international outrage, the resignation of three ministers, and condemnation by the United Nations and international human rights organizations.

Peru’s Ministry of Culture, tasked with protecting the country’s indigenous population, has approved plans by oil and gas giants Pluspetrol (Argentina), Hunt Oil (US) and Repsol (Spain) to detonate thousands of explosive charges, drill exploratory wells and allow hundreds of workers to flood into the Nahua-Nanti Reserve, located just 100 km from Machu Picchu.

The expansion could decimate the uncontacted tribes living in the reserve, as any contact between gas workers and the Indians is likely to result in the spread of diseases or epidemics to which the Indians lack immunity.

Pluspetrol itself recognizes the devastating impact the expansion could have. In its ‘Anthropological Contingency Plan’ the company states that any diseases transmitted by workers could cause ‘prolonged periods of illness, massive deaths, and, in the best cases, long periods of recovery.’

Protests were held around the world against the plans to expand the Camisea gas project in Peru’s Amazon rainforest.

When oil giant Shell first started explorations in the area, it led to the death of nearly half the Nahua tribe. One Nahua man recounted, ‘Many, many people died. People dying everywhere, like fish after a stream has been poisoned. People left to rot along stream banks, in the woods, in their houses. That terrible illness!’

Raya, a Nahua elder who survived contact.

The project violates Peruvian and international laws which require the consent of any projects carried out on tribal peoples’ land.

Last year, protests were held around the world to stop the expansion of Camisea, and more than 131,000 Survival supporters have sent a message to Peru’s President Humala demanding a halt to the oil and gas work on uncontacted tribes’ land. Today, Survival handed the list of the thousands of petition signatures to the Peruvian embassy in London.

As a result of the high profile campaign by tribal rights organization Survival International, local organizations AIDESEP, FENAMAD, COMARU and ORAU, and others, to stop the expansion, seismic testing has been averted from riverways and the location of one well was moved from the land of an isolated tribe.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said today, ‘Thirty years ago workers prospecting for the Camisea deposit penetrated deep into the territory of the Nahua people – and soon after, half the tribe were wiped out by flu and similar diseases. Has the Peruvian government really learnt nothing from history, that it is prepared to risk this happening again for the sake of a few more gas wells?’