A Visit to La Catedral, Pablo Escobar’s Prison, Part II

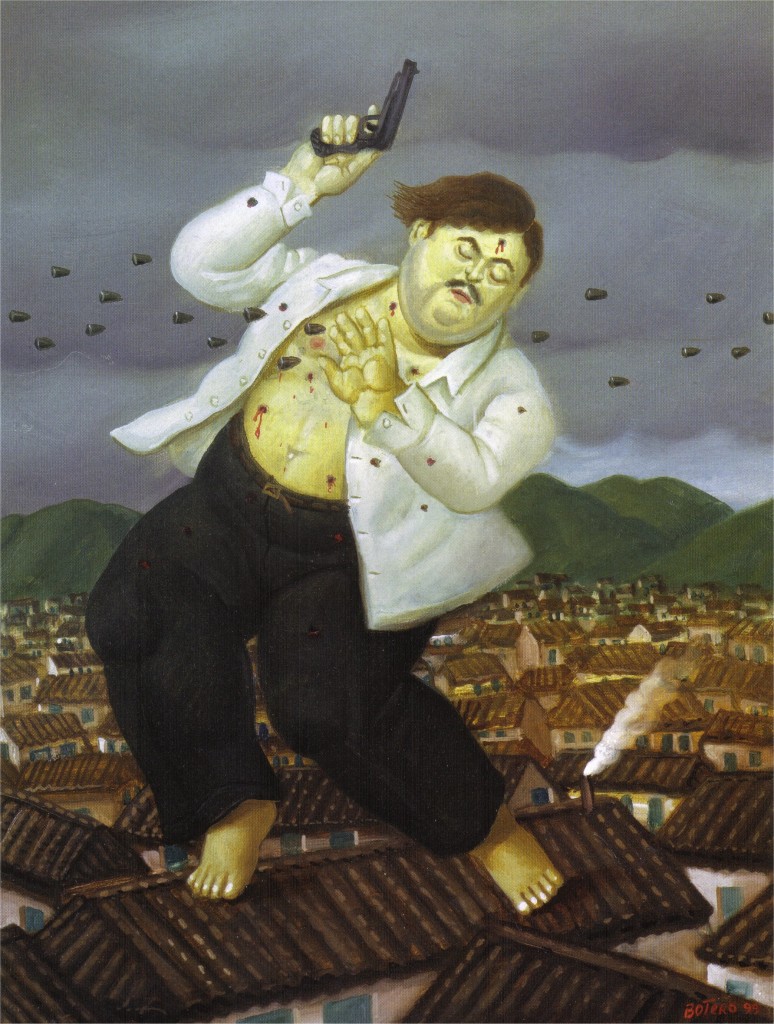

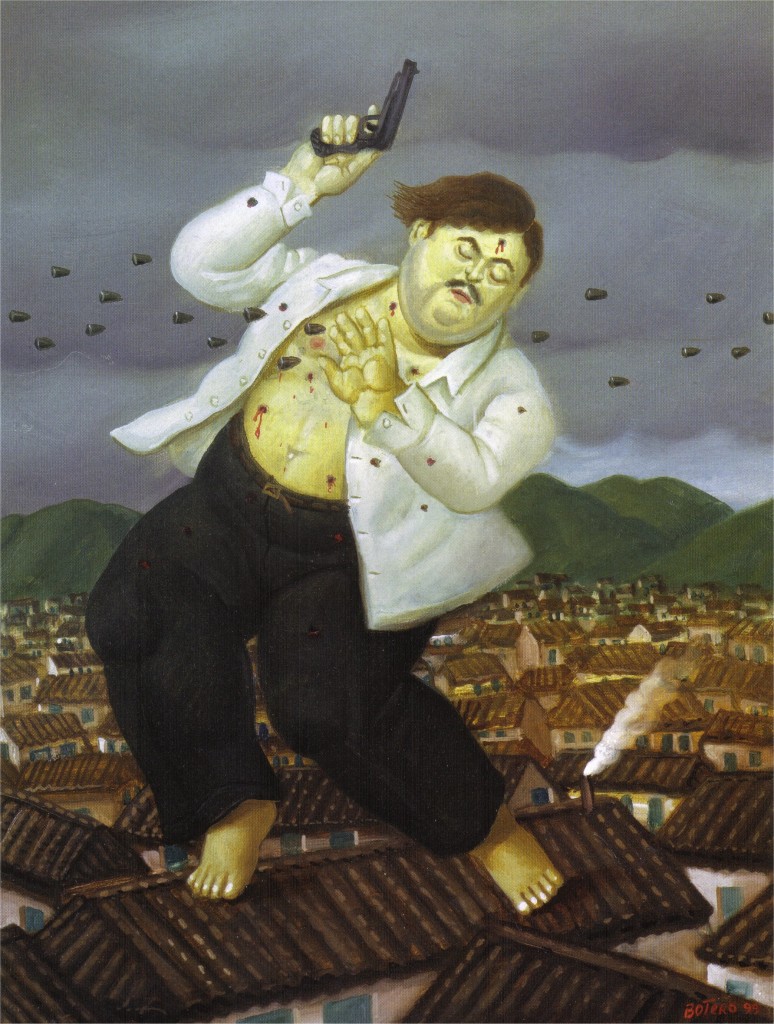

The Death of Pablo Escobar, by Fernando Botero

From my travel journal: Medellín, Antioquia:

Pablo [Ochoa] and I arrive on the dirt road finally at the cluster of buildings that used to house Pablo Escobar, his brother and other Medellin Cartel associates. But the road to the buildings is blocked by an empty kiosk and a gate with a chain lock. No one is manning the kiosk. So we drive further up the hill to a cluster of new buildings, that lie above the prison. The buildings are part of a Benedictine Monastery that was built about five years ago and we part before a small, A-frame chapel built of wood. From inside comes music in form of Gregorian chants. Far below us, in glimpses through the clouds, rise the pink skyscrapers of El Poblado, a wealthy suburb of Medellin.

Inside, the chapel is empty, the music turns out to be a recording and there are wooden pew benches. On a wall is a statue of Christ, surrounded by pictures of the stations of the cross. A 40ish man approaches us. He’s a bit lean and gaunt and tells us he a priest. He offers to give us a tour but not before another cab arrives and a shirtless man gets out, covered in tattoos, makes his way inside, and kneels at a pew. He looks like a gangster and has traveled all of the way up the mountainside to pray. (more…)

Global Warming and the Andes’ Shrinking Glaciers

The stranded ski resort of Chacaltaya, just outside of La Paz, Bolivia

(Excerpt from the book: Peru: Country of Mountains–In the Shadow of Global Warming by Wust Ediciones, 2014)

By Kim MacQuarrie

“And isn’t it a bad thing to be deceived about the truth, and a good thing to know what the truth is? For I assume that by knowing the truth you mean knowing things as they really are.” –Plato

It was a few years ago when I was visiting La Paz, Bolivia, that I first heard the story about an Andean ski resort that had lost its glacier. The resort’s name was Chacaltaya and it had been in operation since the late 1930s. The resort operated upon a glacier about twenty miles from La Paz, a glacier that had been there since the last Ice Age. At over 17,000 feet, the resort was the highest lift-served resort in the world and, since it was the only ski resort Bolivia possessed, the country’s Olympic ski team naturally used to train there. By 1980, however, half of the glacier had melted and the process seemed to be accelerating. By 2009, only seventeen years later, the glacier had completely disappeared. Not surprisingly, Bolivia no longer has an Olympic ski team. Now, like some beached whale, the wooden ski lodge still sits there, forlornly waiting for guests who will never again appear.

The story of the Chacaltaya Glacier, of course, is hardly unique. During the last 10,000 years, since the Earth began emerging from the last Ice Age, Andean glaciers have shrunk by more than 90%. The majority of that shrinkage, however, has taken place during the last 200 years, since the onset of the Industrial Age. And the acceleration is continuing: Andean glaciers have retreated 30-50% in only the last thirty years. Since glaciers are an important source of water for farmers, cities, and towns throughout the Andes, especially during the dry season, it’s a fair question to ask why South America is losing its glaciers in the first place.

Shrinkage of the Chacaltaya Glacier

To answer that, we need to go back two hundred million years, when South America was joined to Africa and both continents were part of a single landmass called Pangea, surrounded by an immense ocean. After Pangea’s breakup, South America split off and eventually became an island, drifting slowly westward on its tectonic plate. For some eighty million years South America remained cut off from the rest of the world, with evolution producing a plethora of unique animals and plants—at first dinosaurs and later an explosion of marsupials. Eventually, the island of South America began colliding with the Nazca Plate, which moved eastwards, hitting South America head on. About 40 million years ago, that collision began to produce a range of mountains that would later be called the Andes. About three million years ago, the oceans sank as the Ice Age began and an isthmus joining North and South America became exposed, allowing a deluge of new fauna to enter the continent. Eventually, about 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, the first people crossed the land bridge and walked into South America.

The world those first inhabitants beheld was one quite different from that of today—it was a world populated by cave bears, saber tooth cats, and sloths that weighed up to 10,000 pounds and were as large as automobiles. The Andes Mountains, meanwhile were still in the grip of the Ice Age with thick, enormous glaciers and abundant snow. Bringing their languages and tool kits with them, the first inhabitants began to explore ever southwards, eventually heading up into the Andes where they survived by hunting and gathering, using furs and fire to protect themselves from the intense cold.

Around 15,000 years ago, as the Ice Age began to retreat, people were forced to either adapt to changing conditions or perish. By now, many of the large mammals had disappeared—due presumably to both intensive hunting and to the changing environment. Around 8,000-10,000 years ago, the first signs of agriculture began to appear. People also began to selectively breed wild guanacos and vicuñas, creating two new species in the process: the llamas and the alpacas. Gradually, hunter gatherers became farmers and farming began to slowly spread through the Andes. With increased production of potatoes, quinoa, corn, squash, peanuts, and chilies, populations soon began to increase and social classes began to emerge. It was during this period that the first temples and ceremonial platforms began to rise, constructed by societies now composed of priests, nobles, artisans, metallurgists, warriors, and peasants working the fields.

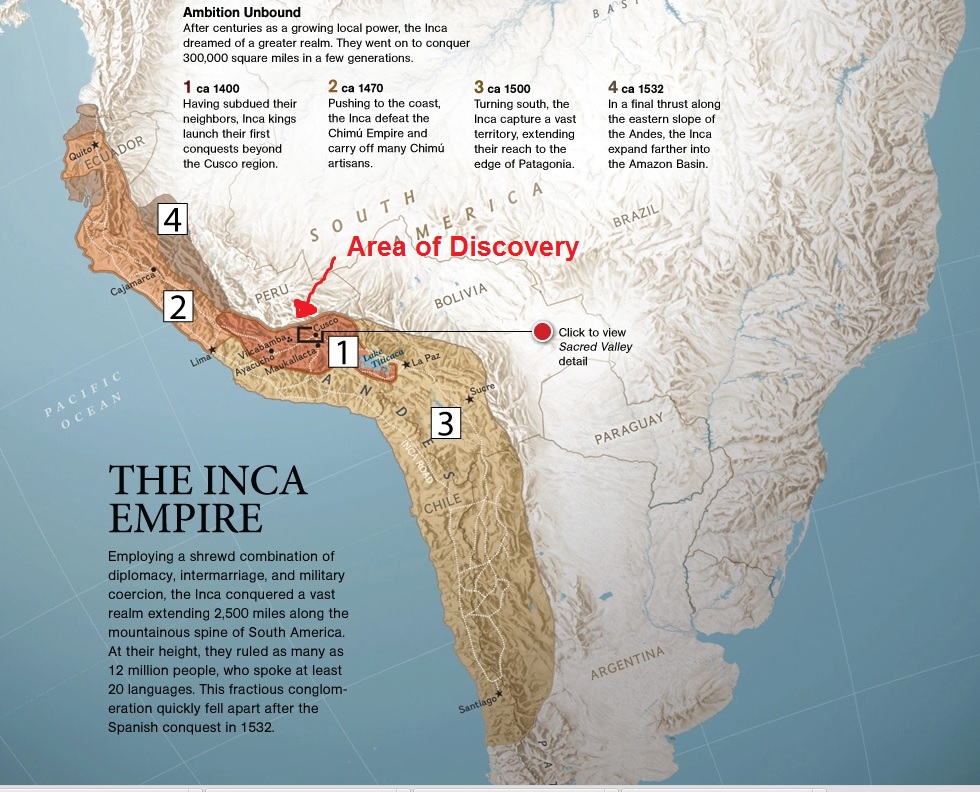

The Andes Mountains, meanwhile, not only collected rain and snow that soon became rivers and could be used for irrigation, but the sheer verticality of the landscape also created what anthropologists call a “vertical archipelago.” The Andes thus resembled an enormous skyscraper—with each “floor” containing different kinds of micro habitats that could be planted with different types of crops. Meanwhile, as the Andes Mountains continued to rise, states and empires rose and fell, eventually producing the Inca Empire, which ultimately spread across 2,500 miles—the largest indigenous empire ever to have existed in the New World.

That the Andes provided an abundance of resources—glaciers being only one of them–and that the native people who lived there had learned to master these resources, is reflected in some of the first reports by Spaniards who began arriving in the early 16th century. Spanish conquistadors quickly discovered a vast system of Inca roads (some 26,000 miles of them, called the Qhapaq Ñan, or “Royal Road”). Alongside the roads stood innumerable warehouses, most stuffed to the ceilings with goods and produce. According to the conquistador, Pedro Sancho de la Hoz,

All the steep mountains…[have roads] of stone…Most of the people on these mountains live on hills and on high mountains. Their houses are of stone and earth [and] there are many houses in each village…Every seventy miles there are important cities, capitals of the provinces, to which the smaller cities brought the tributes they paid with corn, clothes, and other things. All these large cities have storehouses full of the things that are [harvested from] the land….[there are plenty of] vegetables and roots [potatoes, okra, etc.] with which the people sustain themselves and also good grass like that in Spain…There are many herds of sheep [llamas and alpacas], which go about in flocks with their shepherds…The people, as I have said, are very polite and intelligent and always go about dressed [and] with footwear.

Although the Andes provided a rich and varied habitat, the mountains were nevertheless prone to frequent earthquakes, exploding volcanoes, and occasional droughts. The Incas believed that the mountains contained gods and that gods controlled the abundance of food, water, animals, and crops. They not surprisingly made offerings to them. Normally these offerings were of coca leaves, corn, finely woven cloth and animals, such as guinea pigs, llamas, or alpacas. Occasionally, however, at times of great duress, the Incas made human sacrifices. On top of a dozen or more peaks in the central Andes, archaeologists and explorers have discovered the sometimes perfectly preserved bodies of Inca children–offerings made to the mountain gods in a desperate attempt to restore balance and harmony to their world.

Inca Ice Maiden

Five hundred years later, science has provided us with a far deeper understanding of the Andes than the Incas had. We now know that the Andes are partially held up by the force of the impact of the Nazca Plate sliding beneath the South American Plate. The force of that impact, it turns out, acts as a kind of flying buttress, pushing the Andes skywards at the same time as helping to hold them up. The Andes themselves are actually a giant pile of the Earth’s crust, the ongoing remains of an enormous train wreck that is unending, the crust in some places thrust up more than 20,000 feet into the air. Not surprisingly, Peru and the other Andean countries possess great mineralogical wealth—and why wouldn’t they, with so much extra land mass? From the gold and silver of the conquistadors to the lead, copper, zinc, tin, bismuth and molybdenum of today, the mineral wealth of the Andes seems nearly inexhaustible.

The more global view that science has provided has also taught us other things. We now know, for example, that the Andes affect the continent’s entire climate—stopping the trade winds from reaching the Pacific Ocean and forcing humid air to instead dump their water onto the Andes’ eastern flanks. Three quarters of the silt that arrives at the mouth of the Amazon, as a consequence, consists of ground up bits of the Andes Mountains, moved there by a never ending torrent of the Amazon. In addition, because the Andes block the trade winds and because of the cold Humboldt Current sweeping up South America’s coast, Peru and Chile possess enormous stretches of bone-dry coast where it rarely, if ever, rains. Recently, scientists have also discovered that the Andes are a sort of species generator, much like the Galapagos Islands. Since each mountain peak possesses layer after superimposed layer of microhabitats, the mountains themselves resemble a kind of archipelago of islands, with the flora and fauna of each mountain sometimes getting cut off from the others. Thus, the Andes mountain chain acts as a sort of evolutionary pump, supercharging the planet’s biodiversity. Not surprisingly, a county like Peru has some of the highest biodiversity on the planet.

Today, however, the activities of the rest of the world have begun to impact life in even the remotest of Andean villages. And that is primarily because of the dramatic increase in the world’s population. When the first people stepped onto the South American continent, for example, only about four million human beings lived on Earth. Later, as the Ice Age began to retreat, the Earth’s population had increased to about fifteen million—about the present day population of the city of Los Angeles, California. Today, Homo sapiens has reached the extraordinary milestone of more than seven billion members and its population continues to grow. Meanwhile, more than a billion cars now ply the Earth’s highways, spewing out CO2 and contributing to the rise in the Earth’s temperature. Now, not only are glaciers melting throughout the Andes, but so are glaciers around the world, in addition to the rapidly accelerating melting of the twin polar ice caps—the last great thermo-regulators on Earth.

Five hundred years ago, beset by environmental problems they didn’t understand, the Incas made sacrifices to their gods. They did so in order to try and reestablish harmony to their world. Unlike the Incas, however, we have vastly more knowledge about the world than they did and have also created many of our most pressing environmental problems ourselves. And yet we often seem reluctant to do anything about them. If there is one thing we’ve learned, however, it is this: cultures that ignored their negative impacts upon their environments have often vanished, leaving only the ruins of their once magnificent civilizations behind. Will we follow in their footsteps—or will we strive to restore balance to the very planet that has given us life? It’s up to us to decide.