Did a German Adventurer Discover Machu Picchu Before Hiram Bingham? An Interview with Paolo Greer (Part 3)

posted on August 27th, 2008 in Andes Mountains, Archaeology, Did a German Discover Machu Picchu?, Incas, Machu Picchu, Peru, Recent Discoveries

An Interview with Paolo Greer (Part 3)

(To read Part 2, click here)

19) In what year did you find Augusto Berns’ “promotional materials” in Peru’s National Library?

PG: You are referring to the collection of Berns’ papers I mentioned in my article for the South American Explorer… (about “300 items; letters, plans, drafts of advertising brochures, maps and drawings”) that I found in a cardboard box at the Biblioteca Nacional in Lima, Peru.

I finally located that missing trove in July of 1999.

The American explorer, Paolo Greer, on the trail in Peru in 1996

20) In what year did you return to look for the “promotional materials” and discover that they were no longer at the library?

PG: Actually, as is often the case, I got sidetracked.

In 2000, I returned to Peru but spent what time I had in Lima preparing for two National Geographic expeditions.

The idea for the first one came from an earlier article I had written for the South American Explorer magazine about prospecting in the Caravaya jungles of southeastern Peru.

On the second NGS trek, I led the photographers to an ancient city that the Italian explorer, Antonio Raimondi, had visited in 1865 (see “Lost City Of Inca“)

Shortly after that, I was conscripted for yet another excursion, this time with National Public Radio’s ‘Radio Expeditions,’ to the Huaypetue gold fields in order to examine the projected route of the Trans-Oceanic Highway [linking Brazil with Peru and the Pacific Ocean] that led into the Amazon jungle.

With the time that remained, I stayed at a friend’s remote mines in Peru.

Perhaps this is a good place to mention that I have never been paid a cent for my work in Peru, nor for any of what little I have written. I have always researched and explored on my own nickel, either to help friends, for personal curiosity, or both.

I returned to Peru in 2001 but, once again, headed for the high Andes with my amigo to prospect for forgotten mines.

When I got back to Lima, I intended to revisit the Berns’ collection. Instead, I came down with severe case of malaria and it was all I could do to crawl onto a plane back to the States.

The next time I made it to Peru was in 2003.

By then, years had passed and I had new escapades on my mind. Although I consider history fascinating, the ” sticks and stones” adventures are the ones that grab me.

However, Berns’ story once again intervened when, in early August of 2003, my buddy showed me an article from a Cusco newspaper mentioning [the Peruvian historian] Mariana Mould de Pease’s recent “discovery” of Herman Göhring’s 1874 map of Machu Picchu.

I met with the newspaper editor and a reporter to fill them in on the details of Göhring and Berns. I also wrote to Mould de Pease in Lima to introduce myself.

Mould answered immediately, saying that she had just been contacted by the World Monuments Fund and was eager to get the Göhring map published “ASAP,” adding; “In my opinion, the right thing to do is that the two of us are interviewed in order to contribute to the better knowledge of Machu Picchu.”

Nevertheless, I was heading in a different direction, back to the high Andes and my friend’s mines.

I finally met up with Mariana Mould de Pease in Lima on the 6th of October of that same year, 2003.

Although she was obsessed with publishing Göhring’s map, she had not read his [1877] book. Luckily, the Director of the Biblioteca Nacional del Perú had let me duplicate it fourteen years earlier when, after he had assured me that no examples of it remained at the BNP, I was able to show him three separate copies, as well as Göhring’s map, [all of which Greer found in the BNP library].

I photocopied the book for Mould. I also gave her Dan Buck’s 1993 SAE article [“Fights of Machu Picchu”] and the 1999 Via Lactea magazine (which both contained the Göhring maps I had given them, the same as Mariana Mould had recently received from Jorge Flores Ochoa). I also presented her with the pages of Hugh Thomson’s 2001 book, “The White Rock,” relating my earlier research on Göhring and Berns.

More importantly, I gave Mould de Pease the citations for two books I had found about Berns’ “Compañia Anónima Limitada Huacas del Inca,” his company [formed] to sack the ruins, and told her about the twenty-four folders of Berns’ papers in the Biblioteca Nacional.

Since Mould had never seen any of these documents, she was very enthusiastic to “publish our work together.”

I had no intention of writing a book. Mould [already] had one at the printers though; “Machu Picchu y el Código de Ética de la Sociedad de Arqueología Americana” or “Machu Picchu and the Code of Ethics of the American Archaeological Society,” presenting her version of the legal battle [between the Peruvian government and Yale University] over what Bingham had taken to Yale (by the time her book came out, she was able to get an image of Göhring’s map on the cover).

Mould de Pease’s husband had been the Director of the National Library from 1984-1986. When we met, she was also a well-connected political appointee at the INC (Peru’s National Institute of Culture).

Mould assured me that she had the best contacts to recover and preserve the various papers of Berns had found in 1999. At the time, it seemed like a good idea, so I left it to her.

Afterwards, whenever we communicated, I inquired if she had been able to find the missing Berns’ box of letters, drawings, et cetera. For one reason or another, she always said no.

For quite some time, the National Library was in transition from the old building to the new. When I could finally get into the new Biblioteca, I once again tried to locate the Berns’ material. I sought out the librarian in charge of the history collection but the BNP still had no record of Berns’ “300 items”.

To this day, I do not know if the contents of that old box survived the move [from the old National Library to the new]

Earlier, with Mariana Mould’s help, I had also returned to the old library building. There, I showed her the two books concerning Berns’ company’s [desire] to loot the ‘Tombs of the Incas.”

Surprisingly, Mould immediately took photos of the two volumes while expressly forbidding me to do so. Afterwards, the two books were stamped to explicitly prohibit copying them in any form.

21) How did you take notes when you examined this material? By hand with a notebook?

PG: That’s an odd question.

In 1999, I took notes on paper and transferred my scribblings to backup floppies in internet cafes, as well as emailing the retyped data to myself.

My older archives on the Caravaya or Inambari region, alone, add up to hundreds of pounds of paper. If I could digitize it all and back it up as well, I would burn the original hard copy with a smile.

I have spent more time in libraries than anyone I know (who wasn’t paid for it) but [data on] paper is tough to work with and harder to search.

22) You mention that “one folder, alone, had fifty-seven envelopes, addressed to potential patrons.” Did the envelopes contain letters inside? And if so, what was the gist of what the letters said? What was Berns soliciting from these people?

PG: Sadly, those fifty-seven addressed envelopes were empty.

What may have been missing in the box were the envelopes that Berns had already sent. In another folder was a different list of possible clients.

The letters that would have been mailed probably included his five page “Particulars of the Torontoy” and a cover letter. I imagine that he was soliciting investment capital.

Other files in the box at the BNP contained Berns’ original letters.

23) You also mention that there were “seven handwritten drafts of the “Particulars of Torontoy,” Berns’ detailed advertisement to sell his property. From one version to the next, it was telling how he embellished a word here or added another lost mine there.” Was this all written in English? So is that what Berns was up to—lying about fake gold mines so that he could resell the property that he had bought in 1867? Were there dates on these “particulars” or on the letters to patrons?

PG: The date on Berns’ “Particulars” was July 1881. What I saw of his correspondence at the BNP was dated 1880 and 1881.

Judging from Berns’ index of people to solicit, his “Particulars of the Torontoy” was written in English because the United States and Great Britain were where he thought the [best source of] money was.

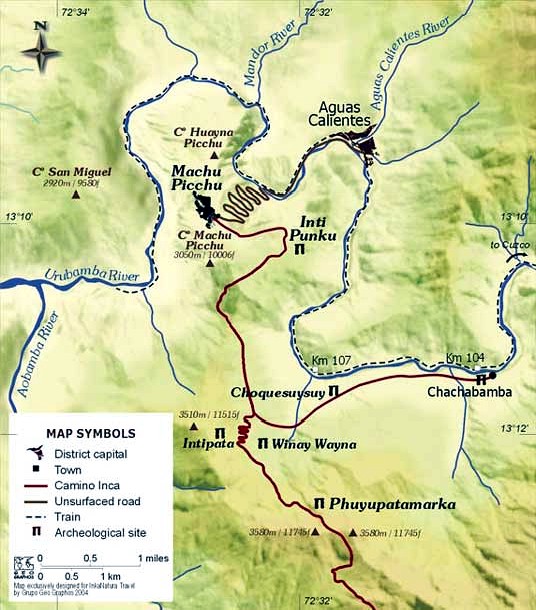

As for fibbing about his gold mines, at first I wondered if Berns had made the common mistake of hoping that whatever gold he’d found in the [Vilcanota/Urubamba] river had originated close to the point of discovery, although I really doubt he panned “colors” anywhere near [the settlements of] ‘Maquina’ or Aguas Calientes.

In any case, when I saw the false hardrock gold veins he had decorated his map with, in the granite slopes near his camp and Machu Picchu, I realized Berns was “a liar standing next to a hole in the ground.”

24) What were the pieces of “corroded, rusty metal” in an envelope addressed to a “Mr. Mahon” all about? What did they signify?

PG: Excellent question. I wish I knew the answer.

The BNP folder #01789 contained an envelope addressed to Mr. George Mahon with rusted pieces of iron a couple of inches long. Since Berns had bothered to send the heavy metal scraps to the States, he must have thought them important.

Actually, I think he was right. Regrettably, the letter of explanation was missing from the envelope. Nor did I did find it in the week I spent attempting to read the rest of Berns’ personal papers.

It is generally accepted that the conquistadors never learned about Machu Picchu. What is not known is when, exactly, Spaniards or Peruvians more recently returned to the ruins for purposes other than cultivation.

I am not referring to the ongoing nonsense about which “Indiana Bingham” or notable Peruvian from the city was first led up the hill by a hearty local. Long before Berns, Vilcanota residents probably plundered the better tombs, shortly after they realized their booty would sell in Cusco.

If Berns’ pieces of iron were not tossed out, along with the rest of his papers, those shards should be evaluated. Their metallurgy might indicate how old they are, what purpose the metal served or if they were simply left behind by earlier grave robbers. Unhappily, that information is less valuable without the missing letter indicating where Berns found them.

25) Why do you say that Herman Göhring had “dispelled his fellow countryman’s [that is, Augusto Berns’] incredible claims of mineral wealth” in 1877? How did Göhring do that?

PG: Göhring dispelled his compatriot’s claims carefully.

Perhaps he simply didn’t want to call his fellow countryman a liar. However, Berns, like Göhring, likely had high political connections, including one or more presidents of the Republic.

Göhring’s explorations, explained in his report, with the exception of the Vilcanota/Urubamba River from Chuquillusca to Colpani, were below Paucartambo, far distant from Machu Picchu. It appears that he came to this area specifically to assess Berns’ claims.

Göhring described the local bedrock, which Berns alleged to be auriferous or gold bearing, as ‘generally sterile granite.’

Although Berns said it contained “wire gold,” Göhring wrote that Media Naranja (what we now call Putucusi, the sugarloaf directly across the river from Machu Picchu) was “porphyry”; i.e. a fine-grained igneous rock, unlikely to contain any metal worth mining, especially by ancient methods.

Göhring said the “slopes of the rock of Picchu” were likewise barren.

While Göhring made no pretense that the granite bedrock contained value, he did write that he was “assured” that the creek running through Berns’ camp had “nuggets of regular size,” a rather strange statement for a mining assessor to make.

Göhring explained the geology in detail and seemed to know his stuff. If he saw nuggets of any size at all taken from what is now Aguas Calientes, he did not mention it.

If someone “assured” me there were plentiful “colors” in the creek and my gold pan told me differently, I would probably believe the pan. Certainly, I would not write a report for the President and include something like, ‘I couldn’t find squat but Augusto assures me there’s beaucoup gold nearby.’

Even with Berns’ phony gold mines exposed, he began negotiating to give the government ten percent of something more enticing [that is, a percentage of spoils looted from Inca ruins]. At least, President Cáceres must have thought so when he made the deal to permit Berns to exploit the nearby ruins.

26) The Peruvian historian, Mariana Mould de Pease, published a letter that she had discovered among the Yale papers of Hiram Bingham in her 2003 book, “Machu Picchu y el Código de Ética de la Sociedad de Arqueología Americana.” The letter was dated June 16, 1887 and was from the office of Peruvian President Andrés Avelino Cáceres. It was addressed to Augusto R. Berns, and you state that the letter gave Berns permission to loot Inca tombs. You also state that Pease “did not then know, because the letter gave no clue, was that the ‘huaca’ to be spoiled was the one we now call Machu Picchu.” How do you know that this letter referred to the ruins of Machu Picchu and not to Inca ruins located elsewhere?

PG: The clues were elsewhere.

What Mariana Mould de Pease found at Yale was a poorly translated or incompletely typed version of President Cáceres’ letter to Augusto R. Berns.

Cáceres gave Berns permission to exploit Inca tombs and structures in the provinces of Urubamba and La Convención in the Department of Cuzco (although the letter that Mould had interestingly left out the word “Urubamba” where Machu Picchu was more likely to be have been described).

Mariana Mould’s book, “Machu Picchu and the Code of Ethics of the American Archaeological Society,” was about her legal arguments concerning Peru’s rights to have returned what Bingham took to Yale. She knew too little about Berns to see an association between him and Machu Picchu, nor did she make any such connection in her book. In fact, Ms. Mould was quite surprised when I told her that Berns lived just across the river from Machu Picchu.

Cáceres’ letter to Berns is part of the story but, alone, it gives no hint of the German’s link to his neighborhood ruins.

Possibly, part of the confusion [arises because] what we [now] know of as “Machu Picchu” was not called that until Hiram Bingham used the term.

In the Inca or Quechua language “Machu Picchu” and “Huayna Picchu” mean “old peak” and “young peak,” respectively. Göhring’s 1874 map, as well as those by [Charles] Wiener (1877), [Antonio] Raimondi (1883+), [Jorge] von Hassel (1904) and [Clements] Markham (1910), all showed Machu Picchu as a “cerro” or hill, just like the name describes.

There are documents by earlier explorers that use words similar to ‘Machu Picchu’ but they do not refer to ruins by that name. I believe it was Göhring who first wrote about the “fortaleza de Picchu” [“the fortress of Picchu”].

Although Native Americans did not call the New World continents the “Americas,” the continents nevertheless existed before the Spanish [arrived]. “Machu Picchu” is a relatively new label, coined long after Augusto Berns’ years of residency at “Maquina” or Aguas Calientes, just below the ruins he called “Huacas del Inca.”

While there is enough evidence to persuade any reasonable skeptic that Berns’ principal target was Machu Picchu, he sought permission from Cáceres to excavate more than that one site, even if his “Tombs of the Inca” were the best of the lot and only a stone’s throw away from his camp.

27) Dan Buck recently wrote a reply to your article on Machu Picchu on this blog and said that “By the way, the 1887 decree mentioned in Greer’s article authorized Berns to excavate in the province of La Convención, a rather large area, but named no specific sites. In other words, the decree has no specific link to the ruin we know today as Machu Picchu, or to any other site for that matter.” Is this true?

PG: Gee, this seems like a repeat of the last question.

Dan Buck has written more about my article on this blog, alone, than all the words contained in my original story. While Buck has been prolific in his invalidation, he offers little evidence of his own as to why he is so fixed in his opinion.

President Cáceres gave Augusto Berns permission to exploit tombs and Inca structures in the provinces of Urubamba and La Convención in the Department of Cuzco. Berns’ property, alone, covered nearly 150 square miles. So, it made no sense to restrict himself to a single ruin when, indeed, there were many.

It is true that Cáceres’ decree did not limit Berns to just the nearby “Huacas” or “Tombs” of Machu Picchu, almost within sight of the German’s camp.

Buck repeatedly insists, on yours and other web sites, that Berns was not at “Machu Picchu”; i.e. “There is no, repeat no evidence that A.R. Berns knew of, visited, intended to loot, or looted Machu Picchu.”

Among other things, I wrote that for many years between 1867 and 1887 Berns maintained a residence two miles from Machu Picchu. During that period, he purposely searched for ruins, using local guides who, like their ancestors before them, were intimate with the area.

Berns was in the business of looting Inca tombs and Machu Picchu was on his doorstep. Since then, millions of tourists have taken the shuttle from the site of Berns’ camp to the ruins, just a few minutes away. In fact, Berns’ base, now commonly known as Aguas Calientes, is officially named “Machu Picchu Village.”

It is specious to say that Berns was not at”Machu Picchu” when neither he nor anyone else referred to the ruins by that name until Hiram Bingham and National Geographic promoted the “lost city,” forty-four years after Berns set up his sawmill close by.

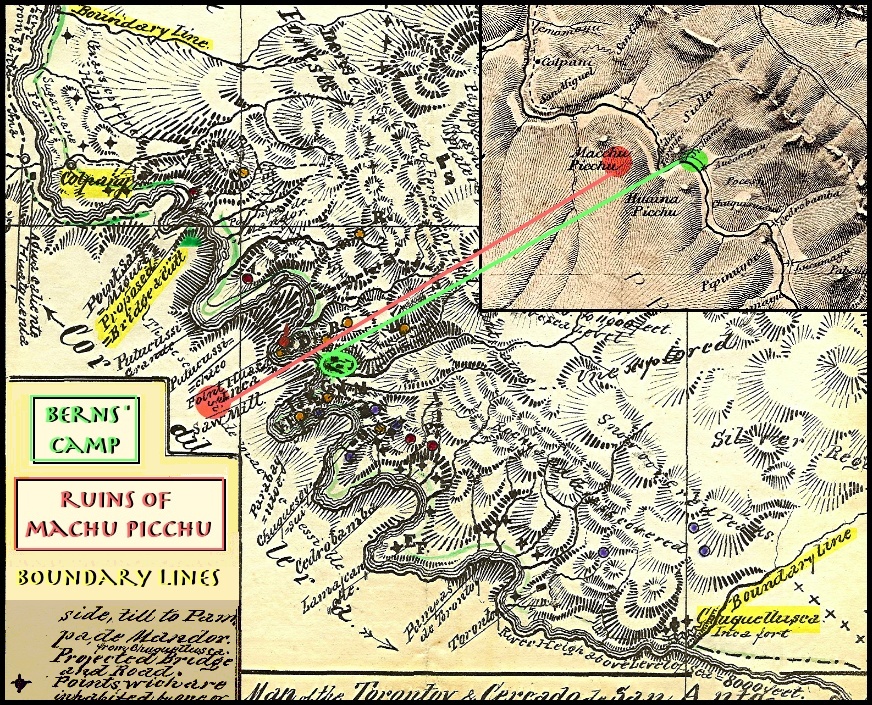

On his map, posted previously in this interview, Berns has marked “Point Huaca Inca” where the bridge now crosses the Vilcanota/Urubamba River just below the ancient city. There are no ruins at that spot unless you stand there and look up at Machu Picchu, which is directly across the river and in plain view.

I have walked from Berns’ sawmill camp to Machu Picchu many times. It takes less than an hour. Most tourists take the brief mini bus ride instead, spend the day at the ruins and return to Aguas Calientes, where Berns lived, with plenty of time to clean up before supper.

Yet Buck is positive that, “The idea that Huacas del Inca refers to Machu Picchu is ludicrous.”

By the way, Dan Buck, like myself, wrote an article on Machu Picchu in the South American Explorer magazine. Also, like mine, his story is available on your blog.

His article is titled “The Fights of Machu Picchu.”

Buck has worked as a professional researcher in Washington, D.C. since the early 1970’s, twenty-five of those years as an investigator for a Congresswoman from Colorado.

The Library of Congress is the greatest archive the world has ever known. It is a “closed stack” library, though. That is, unless the policy has changed since the last time I traveled from Alaska to Washington, D.C. to visit the library, it is difficult to impossible for you or I to check out its volumes.

However, Buck, as a Congressional investigator, could have its historical treasures delivered directly to his desk, along with the contents of many other far flung libraries, books that your home town inter-library loan specialist could not afford to request even if he or she could find out that they existed.

Buck, having long had the sort of advantages that most researchers can only dream about, has become proficient at ferreting out unknown but relevant records.

He also has been paid well for his work and owns the best personal Latin American library I have ever seen.

So, read Buck’s “Fights.”

It swims with names of people who actually had little to do with Machu Picchu, who said they were at the ruins before Bingham and, apparently, were not. Still, “Fights” is an important contribution to the history of Machu Picchu, if only for the prodigious resources that Buck has at his command.

One thing though, at the end of “Fights”, Buck flatly states that, “Ugarte’s 1894 climb now stands as the earliest recorded visit to Machu Picchu.”

How do we know this?

In the University of Cusco’s July 1961 issue of the “Revista del Museo e Instituto Arqueológico,” “an unsigned introductory essay” mentioned “it is known that around 1894, Sr. Don Luis Bejar Ugarte was one of the first to ascend to the marvelous ruins.”

That’s it, Buck’s entire proof.

Despite decades of research on Latin America and extraordinary access to historical documents, Buck offers the reader no more than several lines in an anonymous preface from one virtually unknown magazine.

Not much proof really, but it works for Buck.

On the other hand, how “specific” does he want me to be?

28) In your SAE article, you state that “The government wanted ten percent of the value of any gold, silver or jewels the German [Augusto Berns] found, although it granted the remainder, as well as any objects of copper, clay, wood, stone, and everything else, to Berns without any further obligations, not even custom fees, should he expatriate his treasures.” Where is this information from?

PG: In “Machu Picchu before Bingham,” I cited Mariana Mould de Pease’s 2003 book, “Machu Picchu and the Code of Ethics of the American Archaeological Society” and credited her with revealing Bingham’s copy of a letter to Augusto Berns from President Cáceres.

Since then, Alain Gioda and Lucie Arlandis have found a slightly more complete version that was published in [the Peruvian newspaper] El Comercio on 23 November 1887.

It reads [in English–the Spanish original immediately follows]:

“Supreme Decree regarding the Exploitation of the Huacas and Inca constructions of the provinces of Urubamba and La Convención, Department of Cuzco

[“Huacas” can be translated as “tombs,” “idols,” and/or “sacred sites”]

Lima, June 16, 1887

In light of the request by the engineer don Augusto R. Berns, a German subject, declaring the intention to carry out excavations in pre-Columbian tombs and housing structures located in the province of La Convención and Urubamba in the Department of Cuzco; proposing to give the Treasury part of the value found therein; and requesting special protection for himself and his interests; and considering that the facilities that he requests do not impose any burden on the State, he can enjoy the fruits as a participant of the treasure or values that may be discovered; according to the information provided by the Section of the relevant department, and adopting the indications proposed by the Ministry of the Treasury in the preceding report: accept the proposal with the following conditions:

1.a Don Augusto R. Berns grants to the State ten per cent of the gold, silver and jewelry, or the equivalent of the value in local currency, of all the objects in the aforementioned metals that he finds and extracts from the Inca Huacas and Inca structures in the Department of Cuzco that he proposes to explore and excavate:

2.a All objects of copper, clay, wood and stone will be the exclusive property of Berns, whatever their artistic merit, providing they do not contain gold or silver metal, as the parts in which there are these metals in the objects will be weighed and valued for the effects of the above clause:

3.a The objects of art made of precious metals are permitted to belong absolutely to Berns, prior payment made to the Treasury of the ten per cent corresponding to the State, deducted from the total value of the object after the metal has been weighed and graded:

4.a The aforementioned objects as well as those designated in the second clause, will be at Berns’ complete disposal, and he is free to sell them or export them, with no other tax than that set by the Customs tariff as per the laws in force:

5.a The Government reserves the right to appoint, when it deems convenient, the inspector or auditing commission, to which it will give the necessary instructions, that in agreement with Berns can visit, value and make effective the payment of the ten per cent that corresponds to the State:

6.a The Prefect of Cuzco shall, in the meantime, appoint a person to accompany Berns and witness the excavation works that he executes, providing an account on all the circumstances and work, and a detailed report on what is discovered, in the case that the commission appointed by the Government is not yet present. The wage or fees of this provisional inspector will be paid by Berns:

7.a The Government is under obligation to provide Berns with the law enforcement deemed necessary for the protection of the Enterprise, the protection of his interests and defense of his person and the workers he employs. This force will be remunerated and paid by Berns, as he has offered, through a budget arrangement with the corps they belong to; being also his obligation to provide them with the necessary food:

8.a If Berns forms a Company or Society for this enterprise, said institution will be subject to the conditions hereby stipulated and is not allowed to request a modification, clarification or suspension of the clauses recorded:

9.a All difficulties that may arise in complying with this agreement shall be resolved by the Courts of the Republic, with no recourse of diplomatic claims of any kind.

Grant the corresponding public deed, with prior approval by Don Augusto R. Berns, of the preceding clauses, which are equivalent to official record.

Hereby register and publish —Signature of S.E.

IRIGOYEN”

[Spanish Original]:

“Huacas del Inca.

Decreto Supremo referente á la Explotacion del las Huacas y Construcciones gentilicas de las provincias de Urubamba y la Convencion, Departmento del Cuzco.

Lima, Junio 16, 1887

Visto el recurso del ingeniero don Augusto R. Berns, súbdito alemán, manifestando el propósito de hacer excavaciones en huacas incásicas y en constucciones gentilicas; ubicadas en la provincia del La Convención y Urubamba del Department del Cuzco; proponiendo ceder al Fisco parte del valores que en ellas encuentre; y solicitando especial protección en su persona ó intereses; y en atención á que no imponiendo gravámen ninguno al Estado las facilidades que solicita el recurrente, puede reportarle aprovechamiento como partícipe del tesoro ó valores que se descubrieran; de acuerdo con la informado por la Seccion del Ramo, y adoptando las indicacíones propuestas por el Ministerio Fiscal en la vista que precede: acéptase la propuesta con las condiciones siguentes:

1.a Don Augusto R. Berns cede á favor del Estado el diez por ciento del oro, plata y alhajas, ó en moneda nacional el equivalente al valor de ese tanto, de todos los objectos que de los referidos metales encuentre y extraiga de las huacas incásicas y constucciones gentilicas en el Departmento del Cuzco se propone explorar y explotar:

2.a Serán de propiedad exclusiva de Berns, todos los objetos de cobre, barro, madera y piedra cualquiera que sea su mérito artistico, con tal de no contengan metal de oro ó plata, pues las partes que de ellas se encontrasen en dichos objectos, serán pesadas y valorizadas para los efectos del artículo anterior:

3.a Las objetos de arte de metales preciosos, podrán pertenecer en lo absoluto á Berns, prévia oblacion que haga al Fisco del diez por ciento que corresponde al Estado, deducido del valor total del objeto despues de pesado y apreciada la ley del metal:

4.a Tanto los anunciados objetos como los designados en el artículo segundo, serán de libre disposicion para Berns, quedando con la facultad de venderlos ó exportarlos, sin otro gravámen que el que fija el arancel de Aduana por ser derechos ordenados por las leyes vigentes:

5.a Se reserva el Gobierno la facultad de nombrar, cuando lo crea conveniente, la persona ó comision interventora, á la que dará las necesarias instrucciones, para que de acuerdo con Berns, pueda pasar; valorizar y hacer efectiva la entrega del diez por ciento que corresponde al Estado:

6.a El Prefecto del Cuzco designará entretanto una persona que acompañe á Berns y presencie los trabajos de excavacion que ejecute, dando cuenta de todas las circunstancias con que se realicen, y aviso detallado de lo que se descubriese, en caso de no hallarse aun presente la comision que nombre el Gobierno. El haber ó remuneracion de este interventor provisional será de cuenta de Berns:

6.a El Gobierno se obliga á poner á disposicion de Berns la fuerza pública que crea necesaria para lá protección de la Empresa, el resguardo de los intereses y defensa de su persona y trabajadores que emplee. Esta fuerza será remunerada y pagada por Berns, como lo ofrece, con arreglo al presupuesto del cuerpo á que pertenezca; siendo tambien de su obligacion, proporcionarle la conveniente alimentacion:

8.a En caso que Berns formase Companía ó Sociedad para esta empresa, ella la quedará obligada a someterse á las condiciones estipuladas, sin que sea permitido pedir modificacion, aclaratoria ó suspension de las cláusulas consignadas:

9.a Toda dificultad que se suscite en el cumplimiento de este convenio, será resuelta por los Tribunales de la República; sin que haya lugar a reclamación diplomática de ninguna especie.

Otórguese la escritura pública respectiva, prévia aceptacion de Don Augusto R. Berns, de las cláusulas que preceden, las que tendrán lugar de minuta.

Regístre y comuníquese.–Rúbrica de S.E.

IRIGOYEN”

29) When you say that “Berns’ company, ‘Huacas del Inca,’ was formed to sack Machu Picchu,” do you actually have specific proof that Berns or members of his company visited Machu Picchu and/or looted it?

PG: Would you settle for a couple dozen words from an unsigned, forty-seven-year-old essay in an obscure Cusco magazine?

While the provinces of Urubamba and La Convención have many ruins, Berns’ property extended along the Vilcanota/Urubamba River from Chuquillusca to Colpani. Machu Picchu sits at the midpoint along this stretch, almost directly opposite of the camp that Berns’ kept from 1867 into the 1880’s.

(Above: Bern’s map showing the boundary lines (in yellow) of Bern’s property, across the Vilcanota River from the ruins of Machu Picchu (the red dot). The green dot denotes the location of Bern’s camp and the inset map at the upper right is Herman Gohring’s 1874 map of the Machu Picchu area. Both maps provided by P. Greer; also Greer made the colored markings on the maps. A larger version of the map can be found at the end of this interview.)

For years, Berns explored deliberately for ruins, using local guides very familiar with the area. Berns himself knew the vicinity well enough to precisely mark his map with each of twenty-one separate locations inhabited by resident farmers, upriver and downriver from Machu Picchu.

Berns also petitioned the government to build him a bridge across the river (see his map; “Point San Miguel Proposed Bridge“) to land he did not own, to a place where he did not pretend there were mines, although the link would have given him easier access to Machu Picchu.

After Göhring examined Berns’ mining claims in 1873, he noted the “fort of Picchu” and clearly marked a peak, “Macchu Picchu,” just opposite from Berns’ camp.

A couple of years later, Charles Wiener was upriver in the village of Ollantaytambo. There he was told about a “city” near “Matchopicchu” and “Huaynapicchu.” He did not try to find the town by the “picchus” himself, although he thought it important enough to draw the two peaks and another called “Intihuatana” on his map.

Berns maintained his quarters in close proximity to the ruins [of Machu Picchu] for nearly two decades, years before and after Göhring’s and Wiener’s brief visits. Is it rational to think that two transient explorers were well aware of the site but a resident who intentionally sought out such huacas [Inca burial tombs] was not?

If Berns kept a diary, I have not discovered it. To my knowledge, Berns [also] never owned a camera. Apparently he did not carve his name on the Sun Temple at Machu Picchu either.

In his article, “Fights of Machu Picchu,” Dan Buck gives full weight to a few lines by a nameless author boasting that Lucho Bejar made it to Machu Picchu eighteen years before Bingham. Yet that’s his only proof– a few unsubstantiated words from a single obscure source.

Even so, Dan Buck finds the evidence presented in my article and interview to be “ludicrous” enough to write several thousand words to that effect.

Perhaps, one man’s preponderance of evidence is another’s speculation.

As to whether Berns’ partners visited Machu Picchu:

Berns’ [company] “Compañia Anónima Limitada Huacas del Inca” was formalized in 1887 specifically to exploit [Inca]ruins. While I am convinced that he was at Machu Picchu (there I go again!), I do not have enough information to say that Berns’ allies were there as well.

It does seem reasonable to think that the Vice President of “Huacas del Inca,” Dr. José Macedo– the most enthusiastic collector of Inca artifacts among Berns’ associates in the company [formed] to excavate ruins in the vicinity of Machu Picchu–might have made the effort. However, I have nothing “specific” that places Sr. Macedo there.

Possibly, that evidence will show up in the Berlin Museum where Sr. Macedo sold numerous remarkable relics between 1884 and 1888. Hiram Bingham himself traveled to Berlin in 1913 to see the [Macedo] collection.

Then again, given the [current] political uproar surrounding the “sacking” of Machu Picchu by Hiram Bingham and Yale, I do not expect the present Director of the Berlin Museum [of Ethnology] to be forthcoming.

30) Did Berns ever mention “Machu Picchu” or “Huayna Picchu?”

PG: If he did, I have not read it.

What we now call [the ruins of] “Machu Picchu” is flanked by two prominent sugarloafs, or “picchus.”

In his 1877 report, Göhring referred to the “fortaleza de Picchu” but drew “Macchu Picchu” and “Huaina Picchu” on his map as peaks [that is, Herman Göhring did not indicate the ruins of Machu Picchu on his map].

Likewise, Antonio Raimondi, Jorge von Hassel, Charles Wiener, and Sir Clements Markham marked “Machu Picchu” as only a hill or mountaintop, nothing more.

Augusto Berns named no summits on his map at all, not even Mount Veronica, then known as “Padre Eterno,” even though it reigns supreme over the region.

Berns [also] did not mention Machu Picchu, the mountain, nor did he have any reason to apply those words to the ruins, decades before Bingham gave them that name.

31) When you write that “Berns also recorded having seen a ‘large stone statue of an Inca, one that the locals later secreted away,” where did Berns write this?

PG: In one of Berns’ personal letters I saw at the National Library [of Peru] in 1999, he wrote about ‘a large stone statue of an Inca placed as a sign’ and that, “when he was away, the Indians cut up the statue and threw it in the river.”

I doubt anyone tossed the statue of an Inca in the river. I also have an idea exactly where it stood and where it is now–but that’s another story.

Berns thought the effigy had been “formerly used as a model for the silver molders”.

It is fascinating that Berns thought this and ironic that he said “silver “when he pretended the area was riddled with gold mines, because the stone image might actually have been the form for a golden statue above Pachacuti’s tomb, the “Royal Mausoleum,” in the Sun Temple of Machu Picchu.

In my recent article in the South American Explorer, I wrote: “From the thirty-second chapter of ‘The Narrative of the Incas’ by Juan de Betanzos: “After he [Pachacuti] was dead, he was taken to a town named Patallacta, where he had ordered some houses built in which his body was to be entombed.” … “Inca Yupanqui ordered that a golden image made to resemble him be placed on top of his tomb. And it was to be worshiped in place of him by the people who went there… He ordered that a statue be made of his fingernails and hair that had been cut in his lifetime. It was made in that town where his body was kept.”

32) Do you think more documents will surface, helping to illuminate this period of rather obscure history regarding Machu Picchu and the Vilcanota area? Are you working on any new leads?

PG: Certainly, I look forward to learning more about Machu Picchu than the hackneyed clichés that have often been sold so dearly in the past.

In the recent media frenzy concerning Göhring and Berns, “experts” came out of nowhere, with little or nothing to contribute, simply to join the parade.

Once the spectacle wears off, I hope that more sincere and capable researchers will tell us something we do not know about Machu Picchu before Bingham.

As always, I continue my own research.

Berns was led to other sites. They did not compare to Machu Picchu, nor were they so close to his camp, but they were symbiotic with our famous tourist destination. Some of them, still forgotten, beg for a “scientific discoverer” to initiate the preservation and interpretation of whatever the grave robbers have left behind.

The Llactapata complex, just five kilometers from Machu Picchu, was only recently brought to light by Gary Ziegler and Hugh Thomson.

Although Llactapata was directly associated with Machu Picchu, in 2006 when I was there with Ziegler, the site was still under cultivation and there were signs of fresh looting.

Where are the real heroes or heroines of patrimony when it matters?

33) What have you learned from your long years of research and how that relates to publicizing that research—the rewards and pitfalls of both?

PG: There were rewards?

Just kidding, barely.

I have shared my odd research freely for thirty years. Inexplicably, no one else has done much with it. Even the few who have expropriated my work have made little effort to expound upon it.

Unfortunately, my meager contributions were sensationalized out of proportion. The media seems stuck on this “Indiana Bingham” or “first discovered” nonsense.

I was asked repeatedly what “treasures” Berns found. I think there is enough evidence to allow any unprejudiced reader to appreciate that, after searching for ruins for so long, Berns probably found the jackpot of them all [that is, the ruins of Machu Picchu] , a short hike from his camp. Still, I hope that he did not get much.

Anyway, the better tombs were likely already pilfered by the same locals who guided Berns there, if not by their grandfathers before them.

I have always believed the residents of the Vilcanota River never forgot the location of “Patallacta,” the Inca city that Bingham misnamed “Old Peak”.

On the other hand, Machu Picchu is still being exploited.

While I think that Fernando Astete, the industrious and well-liked current Director of the Machu Picchu Reserve, is doing the best he can under the circumstances, there are other considerable forces at play.

For starters, Machu Picchu is first and foremost a moneymaker.

Most Peruvians cannot afford to see their own famous ruins and less well-heeled foreigners increasingly have to settle for something a little less pricey.

Thanks to previous administrations, there are numerous structures in Machu Picchu that were not there fifty years ago. They have been created from piles of rubble simply to attract more tourists. While the percentage of false constructions absent in older photos is small, how many are too many?

To be clear, I think Machu Picchu is unique and a must see.

I just hope that old “Patallacta” isn’t destroyed for a buck.

Machu Picchu is also a political football but, for now, I will leave that alone.

In any case, perhaps more imminent than the sale of Machu Picchu for a few pieces of silver, is putting it on the market for fool’s gold.

Publishing a ‘Machu Picchu Treasure Map’ depicting numerous bogus gold mines near the ruins could be a disaster.

I have long refused to publish Berns’ plan because I was concerned that certain individuals or the tabloids would use Berns’ schemes to pursue their own, not caring about the fallout such shenanigans might have for Machu Picchu and nearby archeological sites.

Dan Buck recently wrote that “Although Greer has had a copy of said (Berns’) prospectus since 1998, he has never published it, perhaps because it clearly contradicts his speculation. Likewise, he has never published the entire Torontoy map, perhaps for the same reason.”

How’s that for speculation?

Buck has had the same Berns’ prospectus and map for as long as I have. If either contradicted anything I have said, he would have written a few thousand words more in your blog’s comments about it.

Worse, Buck gave a copy of that same map to Federico Kauffman Doig and Mariana Mould de Pease persisted until Kauffman Doig gave it to her.

I have told Mould de Pease many times about my reservations concerning the release of this phony treasure map of the Machu Picchu area. That is why I gave her only a portion of Berns’ drawing. Still, she insists that she wants to publish it before someone else does.

It is ironic that someone who pretends to be the “Queen of Patrimony “ is so eager to publicize a swindler’s map covered with fake gold mines directly across the river from the greatest archeological site in Peru.

Anyway, you asked about the rewards and pitfalls.

These are a few drawbacks that seem especially relevant.

If by “rewards” you mean the media circus relating to Berns’ “discovery” of Machu Picchu before Bingham, I ignored it the best I could.

Despite all, I sincerely appreciate your questions. I wish others had asked even a third as many.

Of course, Machu Picchu still cries out for more research.

It probably always will …

Paolo Greer

(Upcoming: Some original Berns documents & a Timeline of Berns’ activities in Peru)