Did Hiram Bingham Discover Machu Picchu Artifacts–Or Buy Them?

posted on August 11th, 2009 in Archaeology, Incas, Machu Picchu, Peru, Peru-Yale Controversy

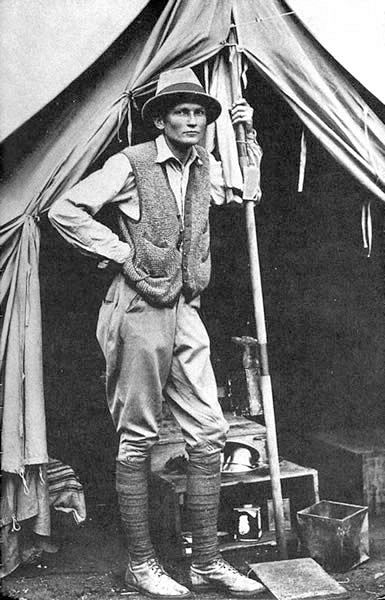

Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu in 1912

Bingham Didn’t Dig Up The Yale Huacos –He Just Bought Them

August 6, 2009

Caretas

By Nicholas Asheshov

Here in Urubamba Hiram Bingham’s reputation has taken a knock in the run-up to the centennial of the discovery in 1911 of Machu Picchu.

The revisionists are saying that Bingham was not just a persistent explorer but also, frankly, a humbug.

Bingham’s economical use of the truth has been compounded by the poorly-advised refusal of Yale University and its Peabody Museum of Natural History to return, as promised, what Bingham’s Yale expeditions dug up in the Vilcabamba 1912-15.

The Peruvian government is taking Yale to court but they’re not pushing it.

Here’s why. None of the good pieces in the Yale Machu Picchu collection were actually dug up by Yale archaeologists.

Instead they were bought by Bingham from Cusco collectors and huaqueros and smuggled out of Peru. Under U.S. law Yale is the legal owner. If Yale people had dug them up, it would be Peru that had the legitimate claim.

The out-whiffling from Peru of the Yale Machu Picchu huacos is much as Luis Valcarcel, an iconic Peruvian archaeologist, maintained noisily nearly a century ago when he and his Cusco Historical Institute took Bingham to court as a grave-robber. Bingham fled, never to return.

The first of at least two major consignments of Inca pottery bought by Bingham and today the pride of the Yale collection consisted of 366 primo pieces purchased by him from Tomas. A. Alvistur who, Paolo Greer, the archivist extraordinaire and systems whiz, tells me was a son-in-law of Carmen Vargas, owner then of the Huadquiña hacienda, just below Machu Picchu.

“Both the Vargas family and Alvistur had well-known collections in Cuzco,” Greer says.

Alvistur had asked Bingham for $2,200 though on top of that, Alvistur warned Bingham in a letter, he would have to add “a great sum to allow the collection to leave, for, as you know, the exportation of ancient objects is prohibited.”

Most of the 5,000-odd items that Yale dug up at Machu Picchu consisted of broken potsherds and bones. One, Richard Burger, of Yale, told me, turned out to be a piece of tough 1915 camp bread mistakenly labeled and coded by a zealous student.

Bingham had quickly realised that others had beaten him to it: Machu Picchu was well-known in Cuzco and had already been sacked. But it didn’t suit either him or Yale to say so. Greer tells me that Bingham visited in 1913 the Berlin Ethnologic Museum to study the collection sold to it in 1882 by Jose Mariano Macedo who, along with Ricardo Palma and other Lima luminaries of the day was a partner of the German adventurer August R Berns (Caretas No. XXXX Notas de Campo, “Huacas del Inca S.A.”).

Bingham forced Alvistur to lower the price on his 366 best pieces: “I realize that the material is worth more than this, and I wish I could pay more, but this is as much as I can possibly offer you.”

Alvistur himself put his collection through customs and onto a ship for Panama. Bingham later thanked the shipping agent for helping to make “Yale an efficient place in which to learn about Peru ancient and modern”.

My source for all this is Christopher Heaney, who I met in the Instituto Bartolome de las Casas in Cuzco a few years ago. Heaney, who consulted with Greer, did a fine job of putting the Bingham smuggling evidence together and published it in The New Republic, D.C., in October, 2006.

Heaney adds that while waiting in Lima in August 1915 for a steamer to Panama, Bingham paid for another “interesting lot of Peruvian antiquities … provided the owner would ship them out of the country.” The owner had them consigned to a fictitious character, “J.P. Simmons, New York.”

Heaney says that Bingham invested $25,000 in purchases, plus costs, of huacos which all went to Yale-Peabody. Bingham, famously, had married money.

If Yale had had any sense it would long ago have returned to Peru the boring bits of academic bones and pottery that its people actually found. But it’s hard for Lima politicos to acknowledge that all the good stuff is protected by a statute of limitations.

Heaney quotes Richard Burger, the Peabody’s curator of anthropology and co-curator of Yale’s Machu Picchu exhibition, as saying that Peru’s bilateral agreement with the United States on antiquities “recognizes the impossibility of disentangling these historical cases and only applies to antiquities that entered the [United States] after 1981.” He also noted, “Private collections were widely bought, sold, and exported early in the 20th century, and museums in Europe and the USA are full of them.”

Heaney quotes a 1953 commentary on the looting of Machu Picchu. “…but where can we admire or study the treasures of this indigenous city? The answer is obvious: in the museums of North America.”

The comment, preceded by quiet thoughts to the effect that no one is to blame, comes from the Diaries of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara.