Englishman and German Claimed to Have Discovered Machu Picchu Before Hiram Bingham (Part 1)

posted on July 4th, 2008 in Andes Mountains, Archaeology, Did a German Discover Machu Picchu?, Incas, Machu Picchu, Peru, Recent Discoveries

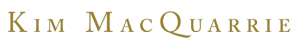

(Above: A view of the Machu Picchu ruins (center left) and Vilcanota/Urubamba River by Hiram Bingham in 1912)

Note: Recent press reports have circled the globe claiming that a German, Augusto R. Berns, discovered and looted Machu Picchu long before the American, Hiram Bingham, “discovered” them in 1911. In an upcoming interview, the American explorer/researcher, Paolo Greer, whose research formed the basis for these press reports, will talk at length about what he actually did or did not discover about Augusto R. Berns. In the meantime, I’m republishing here an article (not previously available on the web) that was written by the American researcher/author Daniel Buck about earlier claims by an Englishman and a German that they had discovered Machu Picchu, not Hiram Bingham. Buck has written his own introductory preface, which follows below… KM

July 1, 2008

“Fights of Machu Picchu,” South American Explorer (no. 32, January 1993), recounts a decades old controversy about who discovered the now famous Inca ruins. The short answer is Hiram Bingham in 1911; the long answer is countless numbers from the 1500s forward. Even though over the centuries others had known of, visited, or even farmed in the ruins before his arrival there July 24, 1911, Bingham is the one who cleared and studied the site, and made it known to the outside world. For that reason, he has come to be called the scientific discoverer of Machu Picchu.

The genesis of “Fights of Machu Picchu” (a pun on Pablo Neruda’s poem, “Heights of Machu Picchu”) occurred in 1987, when National Geographic photographer Loren McIntyre sent me a packet of letters from people who claimed that English missionary Thomas Payne deserved to be credited as the discoverer.

Many individuals assisted me in my research, providing documents, leads, or comments, including Carolyn Anderson, Alfred M. Bingham, Patricia Cerda Pincheira, William W. Evans, Donald Ford, Paolo Greer, John Hemming, Federico Kauffmann-Doig, John B.A. Kessler, Douglas R. McManis, Loren McIntyre, Anne Meadows, Betty J. Meggers, Don Montague, John H. Rowe, W. Stanley Rycroft, Abelardo Sandoval, Stella Mae Seamans, Bill Sillar, and Neil Smith.

The opinions expressed in the article, as well as any errors, are mine.

In recent years, much more has come to light about the post-Inca history of Machu Picchu. One could reasonably assert that Machu Picchu was never lost, just not appreciated. There, but not there; known, but not known. Like dilapidated barns in rural Vermont or abandoned mines in the Rockies.

In Urubamba: Benemérita Ciudad y Provincia Arqueológica del Perú (2007) Leandro Zans Candia presents an excellent summary of references to Machu Picchu from the colonial epoch to the early 1900s, uncovered by such writers as Diego Rodríguez de Figueroa, Fernando J. Soto Ronald, José Uriel Garcia, Luis Miguel Glave, and Maria Isabel Remy. The first person to discover Machu Picchu was there in the 1500s, perhaps not long after the last person had left. Uriel Garcia found a document indicating that in 1776 Machu and Huiana Picchu were sold for 350 pesos, and resold six years later for 450 pesos.

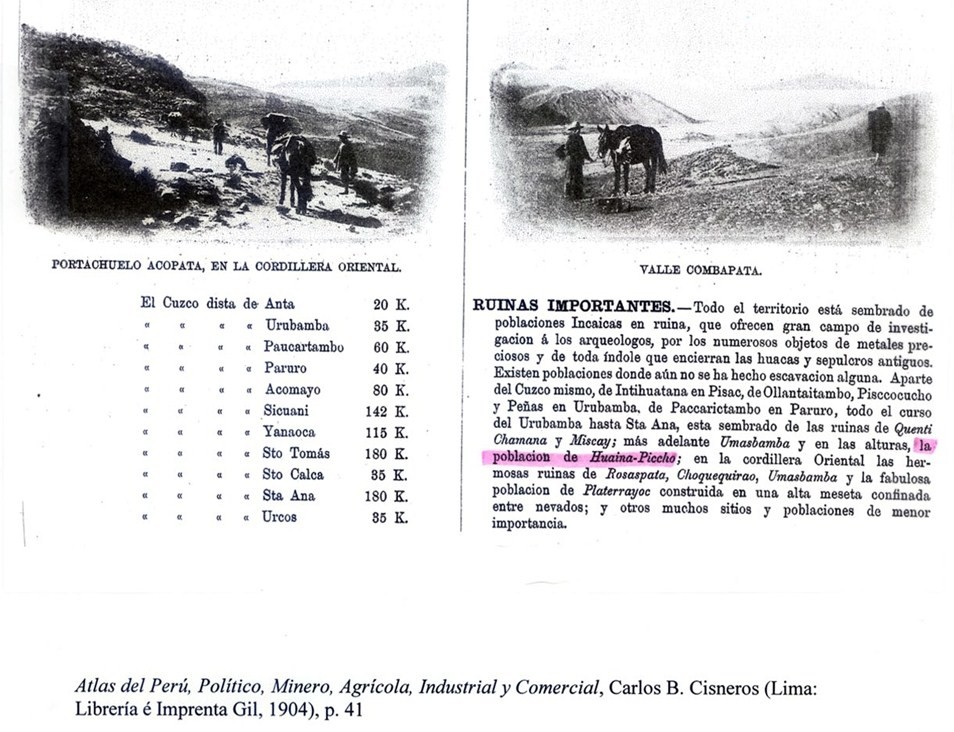

Late last year, while researching at the Library of Congress, I came upon Atlas del Perú (Lima, 1904), by Carlos B. Cisneros, which includes “la población de Huaina-Piccho,” among a long list of archaeological sites in the Department of Cuzco. [See copy and translation at end of Part 1 below] “Todo el territorio está sembrado de poblaciones Incaicas en ruinas,” Cisneros writes, “que ofrecen gran campo de investigaciones á los arqueólogos, por los numerosos objetos de metales preciosos y de toda índole que encierran las huacas y sepulcros antiguos.”

Precisely.

Daniel Buck

FIGHTS OF MACHU PICCHU

By Daniel Buck

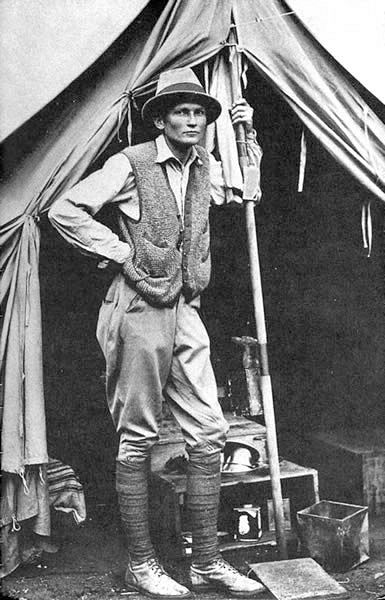

Hardly a lost city is found (or refound, as in the case of the never-really-lost Gran Pajatén) without a reference to Machu Picchu, the Incas’ Urubamba-Valley aerie. The finder is often likened to Indiana Jones, a metaphor not without foundation, inasmuch as Hiram Bingham, the man who discovered Machu Picchu, was a lanky, young, footloose, Yale University professor partial to fedoras, leatherjackets, exploration, mountain climbing, and ladies, not necessarily in that order. In later life, he added aviation and politics to his pursuits. Bingham’s discovery and exploration of Machu Picchu in 1911, recounted in a recent book, Portrait of an Explorer (Iowa State University Press, 1989), by his son Alfred,

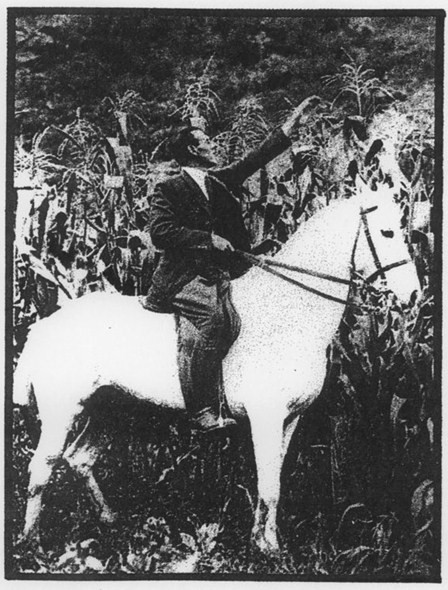

(Above: Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu in 1912)

is famous. Few people are aware, however, of the controversy Bingham generated, although the controversy persists to this day. Whenever the National Geographic Society – which underwrote Bingham’s 1912 and 1915 expeditions to Machu Picchu – publishes a reference to the discovery, it invariably receives letters claiming that Thomas Payne, an English Baptist missionary who lived in Peru from 1903 to 1952, not only found Machu Picchu first, but later told Bingham about the ruined city and even assisted his 1911 expedition.

No contemporaneous evidence has ever surfaced to substantiate the Payne claim, nor has any reference to Payne, who died in 1967, appeared among the Bingham papers. Moreover, Payne’s son-in-law wrote the National Geographic in1983, saying he believed that Payne may have heard about Machu Picchu before Bingham ascended to the city but visited the site after Bingham. The son-in-law surmised that Payne later confused the sequence of events, thus seeding the Payne-Was-There-First claim.

Payne is not the only person who thought he had beaten Bingham to the heights of Machu Picchu. Two Germans made the same boast in 1916. Bingham never–well, almost never–claimed to have been the first person to have gotten wind of or visited Machu Picchu. He usually acknowledged that the ruins had been known to Peruvians, especially to farmers in the Urubamba Valley, two of whom were living among the ruins at the time of his 1911 expedition, and to some residents of Cuzco, especially those who had traveled the valley.

The Peruvians have politely taken to crediting Bingham as the “scientific discoverer” of Machu Picchu, the man who first cleared, photographed, and studied the ruins and, via the pages of the National Geographic, made them known to the outside world. It is in the world outside Peru, however, that the discovery skirmish drags on.

William W. Evans, who met the missionary in 1920 while working on a steamship, is a loyal advocate for Payne. Evans has written that Payne told him that he “operated a Mission Farm near Cuzco and…in 1905 he discovered ‘Machu Picchu’ and made the climb. Many years later, Bingham came by his farm and Tom told him exactly where the ruins were located and even loaned him his pack mules to make the climb.”

In an undated, five-page memorandum, “The True Story of the Discovery of Machu Picchu,” Evans recalled that in 1920 he was working as a purser on a steamship, where he first met Payne, who was returning to Peru after purchasing equipment and supplies in New York for his farm mission at Urco, near Cuzco. During the 1980s, Evans took up the cause with a fervor, peppering the National Geographic Society, various magazines, and Machu Picchu researchers with letters on Payne’s

(Above: The English Baptist Missionary, Thomas Payne)

behalf. Evans summarized the story in his memorandum:

“In 1903 an American Gold mining prospector named Franklin met Tom Payne on a Trail and he told him that while he was riding down an old Inca road he noticed some peculiar markings on a mountain in the distance. At this time Tom was too busy with his Farm and Mission to venture the trip alone. However, in 1905-6 a British missionary named McNairn came by Tom Payne’s Mission and Farm and be asked if he didn’t want to go along and see what the ruins were on the mountain side, which he did.

Many months later, McNairn met a Scotch mining engineer named Stapleton and he told him about his climb up to the Ruins with Tom Payne. Some years later, this mining Engineer Stapleton met Bingham and told him about Tom Payne and McNairn’s discovery and that be should contact Payne and he would tell him all about the adventure.

In 1910 Bingham finally arrived at the Payne Farm and Mission and Tom told him exactly where to find `Machu Picchu’ and even rented him Mules for the trip. This Engineer Stapleton became Bingham’s Guide and interpreter as Bingham couldn’t speak Spanish.”

To buttress the Payne story, Evans quoted from letters from several family members, including Payne’s wife (who died in 1982, at age 95) and daughter, to the effect that in 1906 Payne had climbed to Machu Picchu with McNairn, and that in 1910 Bingham had visited Payne and learned from him how to reach the lost Inca city. Evans also called on three educators who had lived in Peru and had known Payne. Evans quoted one of them, Dr. Herbert Money, as writing, “I knew Tom Payne personally and heard from his own lips his account of his visit to ‘Machu Picchu,’ at least 5 years before Hiram Bingham’s famous expedition.”

The Payne story became firmly established in Protestant missionary lore. In a 1981 book, Eternity in Their Hearts, Don Richardson related the story as told to him in 1978 by a Seattle doctor Daniel (or David as he is also cited) Hayden, who knew Thomas Paine [sic] personally over a period of years in Peru [and who] affirms that Paine – a humble man beloved by Inca descendants throughout Peru – chose not to try to correct Bingham’s `oversight.’ Paine remains just one of innumerable Christian missionaries whose contributions to science have been denied recognition by men of science.

According to the Hayden-Richardson version of events, “in the early 1900s a Scottish Presbyterian missionary named Thomas Paine befriended some Quechua Indians and learned about the ruins from them. Paine visited the site.”

After the “Royal Archaeological Society” (presumably the Royal Geographical Society, as there is no record of any such archaeological organization) declined the missionary’s recommendation to explore the ruins, Bingham “heard of Paine’s discovery” located the city, and became “world famous” as the discoverer of Machu Picchu.

Dr. W. Stanley Rycroft, another missionary, wrote to Liberty magazine in 1985, taking exception to an article crediting Bingham with the discovery. Dr. Rycroft said that in 1903 Payne had come to Peru, where he worked as an “agricultural missionary” at the “Urco Farm” run by the Evangelical Union of South America, and that:

“Mr. Payne told us of his climb to Machu Picchu, together with an American engineer named Franklin and a Quechua Indian in 1906. Mr. Payne wrote to the Royal Archeological Society in Britain recommending that an expedition be sent to explore the ruins.”

In 1940, the Rev. Stuart McNairn, then General Secretary of the Evangelical Union of South America, spoke over the B.B.C. in London, and dramatized the climb of Payne and his companions up Machu Picchu in 1906.

No record of the BBC broadcast or letter from Payne to the Royal Geographical Society has ever been found.

Another Payne partisan, Frank Zeoli, cited Richardson’s book in a letter published in the September 1982 National Geographic. Zeoli’s letter contained a number of inaccuracies and led to a correcting letter from Payne’s son-in-law, Dr. J.B.A. Kessler, a retired missionary living in Costa Rica. According to Dr. Kessler, his father-in-law–whose full name was Thomas Ernest Payne–was an English Baptist, not a Scottish Presbyterian, who had worked in Peru from early 1903 to 1952, until 1908 in Cuzco, and thereafter at the Urco Mission Farm north of Calca. (For a brief history of the Urco farm and Payne’s work there, see Dr. Kessler’s A Study of Older Protestant Missions and Churches in Peru and Chile, Goes, Netherlands, 1967).

Dr. Kessler summarized the discovery story “as told to me on repeated occasions by my father-in-law.” In 1904, Payne had encountered

“an American mining engineer named Franklin on a road near Cuzco… [Later] Mr. Payne came to see Franklin quite often and Franklin told him how once while riding along an Inca road near the great loop of the Urubamba river he had seen Inca ruins on the saddle between Huayna and Machu Picchu. According to my father-in-law, together with a colleague called Stuart McNairn, who indeed was a Scottish Presbyterian by origin, he set out to explore [the ruins] in 1906…. They spent the night at the ruins and descended the following day.”

(Next: Part 2)

(Below: A copy of the 1904 Atlas del Perú by Carlos Cisneros (published five years before Hiram Bingham’s first visit to Peru in 1909), which mentions the Inca ruins of “Huaina-Piccho”):

“The whole area is littered with ruined Inca villages that offer fertile material for the investigations of archaeologists because of the numerous objects of precious metal and other kinds of things that surround the ancient idols and tombs. There are [Inca] villages where there have still been no excavations. Besides Cuzco itself, there are Intihantana in Pisac, Ollantaitambo, Pisccocucho and Peilas in Urubamba, [and] Paccarictambo in Pararo; the entire length of the Urubamba until Santa Ana is littered with the ruins of Quenti, Chamana,and Miscay; further along are Umasbamba and in the heights, the village of Huaina-Piccho; in the Eastern Cordillera are the beautiful ruins of Rosaspata, Choququirao, Umasbamba, and the fabulous village of Platerrayoc, constructed on a high mesa surrounded by snow-covered mountains; and many other sites and villages of lesser importance.”