Englishman and German Claimed to Have Discovered Machu Picchu Before Hiram Bingham (Part 2)

posted on July 9th, 2008 in Andes Mountains, Archaeology, Did a German Discover Machu Picchu?, Incas, Machu Picchu, Peru, Recent Discoveries

Fights of Machu Picchu

By Daniel Buck

Part 2

Dr. Kessler continued his research at the McNairn family library in England, however, and in March 1983 he wrote to Carolyn Anderson, the National Geographic’s resident authority on Machu-Picchu-Discovery claims, to report his startling conclusion that his father-in-law had been mistaken…

During a visit to England the previous November, Dr. Kessler had found a 1946 book, The Lost Treasure of the Incas, by McNairn (whom Dr. Kessler described as “unlike my father-in-law…a careful writer”), who said that:

“old Franklin the Scot [told him] of having once, from the top of a mighty cliff high above the roaring stream of the Urubamba…seen away across the gorge, hidden in the jungle, walls and fragments of buildings of evident Inca work. He believed there must be some city there and be begged us to go and explore. But in those days we had no time for seeking lost cities and we thought little of the old man’s tales. Years later professor Hiram Bingham of Yale University came seeking the lost city…. And there in the gorge of Urubamba, in the heights of Torontoy two thousand feet above the river in the very spot where the old Scot had told us he had seen the ruins, professor Bingham found the lost city of Machu Picchu….”

Dr. Kessler found missionary records indicating that McNairn had lived in Peru from 1904 to 1911, and “therefore [it is] quite possible that he was riding with my father-in-law in 1904 as Mr. Payne said to me, when he first saw Franklin.” Dr. Kessler also spoke with the daughter of an American mining engineer who “had told her that an old prospector had come to stay with the missionaries in Cuzco and that what he had told them about Inca ruins was passed onto Bingham.” Dr. Kessler noted that in Bingham’s Lost City of the Incas, the Yale explorer did mention that “one old prospector said there were interesting ruins at Machu Picchu, but his statements were given no importance by leading citizens.”

(Above: An homage to Hiram Bingham plaque, at Machu Picchu, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of its discovery in 1961)

In his 1983 letter to Anderson, Dr. Kessler concluded that “where my father-in-law’s story seems to be seriously inaccurate is in claiming that he and McNairn went to Machu Picchu before Bingham did so. He may have become confused by the fact that in 1906 or 1908 Franklin told him about Machu Picchu.”

Even if Franklin had seen a ruined city, which one he saw is by no means certain. McNairn claimed that Franklin saw Machu Picchu “in the heights of Torontoy two thousand feet above the river,” but Torontoy is up the Urubamba Valley from Machu Picchu. In fact, it is closer to Ollantaytambo than to Machu Picchu, and back then the valley was full of little-known ruins. Approaching Torontoy while working his way down the east side of the river in 1911, for instance, Bingham noted the small fortress Salapunco as a new find: “When we first visited Salapunco no megalithic remains had been reported as far down the valley as this.”

Bingham also spotted “[a]cross the river, near Quente, on top of a series of terraces…the extensive ruins of Patacalla…an Inca town of great importance.” At Torontoy itself, he reported, lay “another group of interesting ruins, possibly the residence of an Inca chief.” Finally, Bingham said that on “the opposite [west] side of the river [were] extensive terraces and above them, on a hilltop, other ruins first visited by” two advance members of his expedition. (Inca Land, Boston, 1922, pp. 209-13).

Unknown Inca ruins continue to be discovered in the Urubamba Valley. Just ten years ago, for example, Peruvian archaeologists found an extensive agricultural and burial site directly below Machu Picchu. (“A Sister City at Machu Picchu,” Newsweek, July 4, 1983, p. 76.)

Dr. Kessler’s reversal, however, did not cool the ardor of other Payne boosters, including Evans, who achieved a victory of sorts when a capsulized version of Payne’s discovery claim was cited (p. 639) in the addendum to the revised paperback edition of John Hemming’s Conquest of the Incas, [in 1993] the definitive history of the fall of the Inca empire.

Whether Franklin saw a ruined city from a distance or actually visited it is also a matter of disagreement. Stratford D. Jolly, an English treasure hunter who led a late-1920s expedition to dig up the legendary Jesuit gold treasure at Sacambaya, near Cochabamba, Bolivia, said that Franklin explored the ruins: “The first known discoverer [of Machu Picchu],” Jolly wrote, “was an English prospector named Franklin, who explored it in the early `eighties of the last century” (South American Adventures, London, c. 1930, p. 62).

In several accounts, Franklin the Scot is confused with an American named Daniel Casey Stapleton, the Illinois-born son of a Welsh immigrant, who represented various business interests in South America in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

According to Evans, Stapleton’s daughter Stella Renchard had been working on her father’s diaries, which might have shed more light in his role in the Machu Picchu discovery, but she died in an automobile accident in Saudi Arabia in 1982, before she could finish her work. Mrs. Renchard, wrote Evans, had told the Payne family that:

“…her father…a Scotsman had worked as an Engineer in Peru and had met Tom Payne at the Urco Farm and Mission. He had also met Hiram Bingham and for six months acted as Bingham’s guide because Bingham did not speak Spanish or Quechua.

Bingham never gave [Mrs. Renchard’s] Father any credit for all the time he gave him in any of his publications. He also advised him to get in touch with Tom Payne and be would tell exactly where to go to find the ruins.”

In 1910, Mr. Stapleton met Hiram Bingham and as Mr. Bingham did not speak the language, offered to help hire mules and accompanied him on his early trips. Stapleton led Mr. Bingham to Choque Quirau and many other ruins and also told him to get in touch with Mr. Payne at the URCO Farm. This Mr. Bingham did and my father-in-law told him exactly how to get to Machu Picchu and rented him mules to take him there as well as sending his muleteer along with him.”

Bingham, however, was back at Yale University in 1910. He had been in Peru in early 1909 and, while traveling by mule from Cuzco to Lima, visited the ruined Inca city of Choqquequirau near Abancay in February at the insistence of J. J. Nuñez, the prefect of the department of Apurimac, who had organized a treasure hunt to the ruins. Bingham’s foray at Choqquequirau ignited an interest in Peruvian archaeology, which led to his return in June 1911 as the leader of the Yale Peruvian Expedition and to the discovery of Machu Picchu.

In Across South America (New Haven, 1911), Bingham recounted the Choqquequirau excursion in great detail, including the fact that Nuñez had organized and provisioned his party. The only other American on the trip was Bingham’s traveling companion, Clarence Day. No reference to Daniel Casey Stapleton appears anywhere in the book, although Bingham did mention that:

“Two American civil engineers whom I met in Arequipa had told me that the journey from Cuzco to Huancayo would be full of troubles and countless difficulties…. They had not been over the road but had lived for months in Cuzco and had `heard all about it….”

Stapleton might have been one of the two Americans Bingham encountered in Arequipa, and perhaps their conversation on the rigors of mule travel in Peru later became the foundation for family stories that Bingham was inexperienced and had been guided to Choqquequirau by Stapleton. In a later retelling, Choqquequirau might have become Machu Picchu.

Stapleton’s granddaughter Stella Mae Seamans, however, recalls that her grandfather lived mainly in Ecuador (Above: The American engineer, Daniel Casey Stapleton)

and Colombia, not Peru. She has found no references to either Peru or lost cities in his letters to his wife, which Mrs. Seamans thinks might be the diary referred to by Evans. Although she remembers her mother, Stella Renchard, saying, “Machu Picchu, your grandfather knew about that for a long time,” Mrs. Seamans doesn’t “think he discovered anything.” (Stella Mae Seamans telephone conversation with the author, March 1, 1990).

German Claims to Discovering Machu Picchu

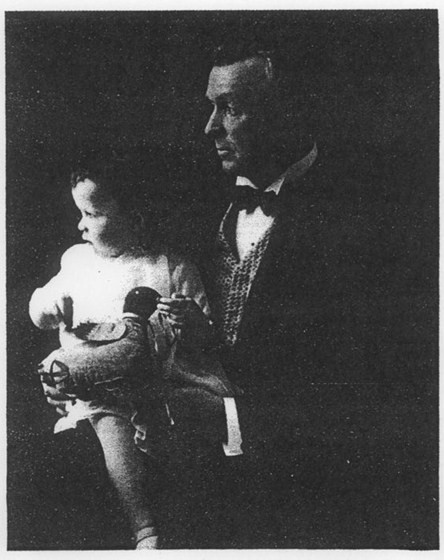

Americans and Britons were not the only dissenters to Bingham’s claim. The first attack on Bingham’s announcement of his discovery of Machu Picchu was reported on September 8, 1916, by The New York Times in a story headlined “Scoffs at Bingham’s Inca City Discovery.” In a sarcastic letter published the previous day in a Berlin newspaper, German mining engineer Carl Haenel ridiculed Bingham’s claim and asserted that Machu Picchu, which he called “Tampu Tocco,” had been discovered by another German, J.M. von Hassel. Haenel asserted that he, himself, had also beaten Bingham to the ruins with an ascent in 1910, and that but for the intervention of World War I, he would have led a German expedition to Machu Picchu.

“I have read with unconcealed astonishment,” fumed Haenel, “reports of the alleged discovery of the holy city of the Incas.” Haenel described Bingham as “a violent anti-German” and a “worthy compatriot” of other, unnamed fraudulent American explorers.

Haenel added that von Hassel had written up his discovery in a 1909 monograph, “Vias de la Montaña,” published in Iquitos. “Whether the shrewd Yankee told [lost-city-discovery] fiction to the Peruvians of Lima is another question, for every halfway educated Peruvian knows of this monograph….” In an apparent contradiction, however, Haenel proceded to say, “neither Hassel nor I beat the self-advertising drum, nor was it the purpose of our journeys at that time to make further particulars known of our trip….” Haenel then went back on the attack, charging that Bingham had not only stolen von Hassel’s thunder, but had relied on his reports:

“I am firmly convinced that Hiram Bingham not only made use of our silence, but that he availed himself of Herr Hassel’s sketches and notes of paths through the jungle in order to reach his goal which be afterward trumpeted as a great `discovery.’”

Jorge von Hassel, as he was known in Peru, served in the early 1900s with the Junta de Vias Fluviales, which had been established by the Peruvian government in 1901 to survey the riverine eastern lowlands in an effort to open the region to commercial development. Von Hassel wrote a series of reports and monographs, among them “Vias de la Montaña,” a 109-page study of possible rail, road, and river routes in the eastern Peruvian jungle which–Haenel’s assertion notwithstanding–contains no mention of von Hassel’s having sighted or discovered a ruined Inca city. The only reference even faintly relevant appears in Table LII (p. 100), “Mollendo a Cuzco,” in which von Hassel listed the altitude, and sometimes the distance from Mollendo, of 50 localities from Cuzco down the Urubamba Valley to the Rio Ucayali, the Amazon, and, finally, to Para (Belém), Brazil.

Between Ollantaytambo and Santa Ana, which are the sites above and below Machu Picchu, von Hassel listed something he called “Escaleraincaica,” at 2,200 meters. With the Machu Picchu ruins at 2,400 meters and the railroad station on the bank of the Rio Urubamba at a bit below 2,000 meters (“Inca Trail,” SAE, 1978), von Hassel’s “Escalera incaica” might have referred to the andenes, the terraced fields, that scale the mountainside from the valley to the ruins. But in another report, “Cuadro de Distancias,” published two years earlier, von Hassel wrote that “Escalera Incaica” was 63.6 kilometers down the valley from Ollantaytambo and 23.7 kilometers up from Santa Ana, which would place it about 20 kilometers below Machu Picchu.

Von Hassel’s other publications published in Peru during his service with the Junta de Vias Fluviales contain no apparent, cartographical references to Tampu Tocco, Machu Picchu, or any comparable ruined city. His 1904 map “Archivo Especial de Limites de Croquis de la Regi6n Madre de Dios-Manu Paucartambo y Ucayali” showed no named site in the Urubamba Valley between Carpamayo and Huadquina, where Machu Picchu is found.

In his “Informe del 2. Ingeniero de la Comisión Exploradora del Istmo de Fiscarrald,” El Istmo de Fiscarrald (Lima, 1904), von Hassel referred (p. 100) to certain legends that during and after the Spanish conquest, Cuzco and Urubamba Indians fled to forested regions where they built isolated cities. Von Hassel named only one such ruin that he knew of, at Tonquini near the Pongo de Mainique, considerably down the Urubamba Valley from Machu Picchu.

Von Hassel’s short memoir of his life as an explorer in Peru, Hechos y Sueños, Episodios de la vida del Explorador Von Hassel (Lima, 1905), contained only a brief mention of the Urubamba region, a reference (pp. 50-1) to a trip one June from Cuzco to Urubamba, and then north to the Ocacamba Valley, where he encountered a colony of German vegetarians, up to the Rio Yanatili, which he followed to the confluence with the Rio Urubamba in the eastern lowlands north of Echaite. No mention of Inca ruins.

In “Las Tribus Salvajes de la Región Amazónica del Perú, Boletin de la Sociedad Geografica de Lima (vol. 17, no. 15, 1905), von Hassel again referred (p. 46) to the “fortaleza incaica de Tonquini (Baul de Inca),” which he believed had been built by a rebel Inca who had fled the Spaniards, in a Machigangas region of the lower Urubamba. Further along in his report, in a paragraph (p. 54) entitled “Ruins Incaicas,” von Hassel summarized his knowledge of Inca ruins from his ten years’ exploring in the Peruvian montaña and Amazonian regions:

“The principle monuments in the Andes of the Inca era are the following: Inca roads from Paucartambo to the Madre de Dios (refer to the report of the von Hassel expedition); the Inca road [from] Cuzco, Amparay, Chimur to the headwaters of the Manu, Camisea, Ticumpinea, etc. (See the von Hassel report.) The andenes in the Yavero valley, the Inca road from the Urubamba valley towards the Pongo of the Mainique or Tonquini, andenes and other indications of the Inca era in the Timpia and Ticumpinea valleys with the carvings of the sun and the moon on a rock near Pangoa. Inca roads to the right and left of the Marañon. At Cumari and Picria on the Ucayali were the ruins of buildings that contained copper axes. The Vilcabamba ruins at Intipampa, Rio Piccha.”

Von Hassel did make one major lost-city discovery, although it has never been verified. He claimed that, on the island of Tumpinambaranas, formed by an arm of the Rio Madeira where it joins the Amazon, he found “gigantic ruins demonstrating that there was a civilization similar to the Incas.” Von Hassel thought that the site should be subjected to “a serious study, which might shed some light not only of the ‘Gran Paititi,’ but also on the origin of the first Inca, Manco Capac.” (Von Hassel’s suggestion that the ruins at Tumpinambaranas might illuminate the origin of Manoo Capac is a classic example of cradle fever, a virus that has heated the imagination of many an Andean and Amazonian explorer, including Col. Percy Fawcett, Gene Savoy, and Hiram Bingham: “Whatever it is I’ve found it was so lost it must have been the cradle of an unknown, but important civilization”).

Von Hassel reiterated his story about the flight of the rebel Inca and the lost Inca city in yet another report, “Informe del Jefe de la Comisión del Alto Madre de Dios, Paucartambo i Urubamba por la Via del Cuzco,” included in Ultimas Exploraciones Ordenadas por la Junta de las Fluviales a los Rios Ucayali, Madre de Dios, Paucartambo u Urubamba (Lima, 1907):

“According to a local legend, 4,000 Inca soldiers, commanded by a prince of the royal house, descended the Urubamba fleeing the Spanish conquest. On the side of the Tonquial mountain, I saw the ruins of an Inca city and, right where the Yavero flows into the Urubamba, are found gigantic stones carved with inscriptions.”

In this same report, von Hassel noted (p. 302) that he had explored the Urubamba Valley as early as 1898, and that he had studied “various Inca roads on the left bank of the Urubamba.” It was on the 1898 expedition that he found one such road “and the remains of an ancient fortress, of the same epoch, near the Tonquini mountain, which had been shown to me by a rubber worker of [Carlos] Fitzcarrald, named Simon Hidalgo. In the same manner, I found Inca hieroglyphics near the mouth of the Rio Yavero.”

The day after Carl Haenel’s heated rejection of Bingham’s discovery claim, The New York Times published Bingham’s reply that he had “never heard of the two Germans” and that he had “never seen their articles, maps, or notes.”

The same day as the first Times story, The New York Evening Post had forwarded the article to Isaiah Bowman, the geologist on the 1911 Yale expedition, requesting his comment on “the merits of the controversy.” Bowman declined to make a public statement, replying cautiously that mixing “politics and science…would arouse antipathies between good friends. It would help perpetuate part of the ill-feeling of the war.” But he did allow that “Professor Bingham’s discoveries are sound–of that you may be quite sure. I know his work intimately.”

(Next: Part 3)

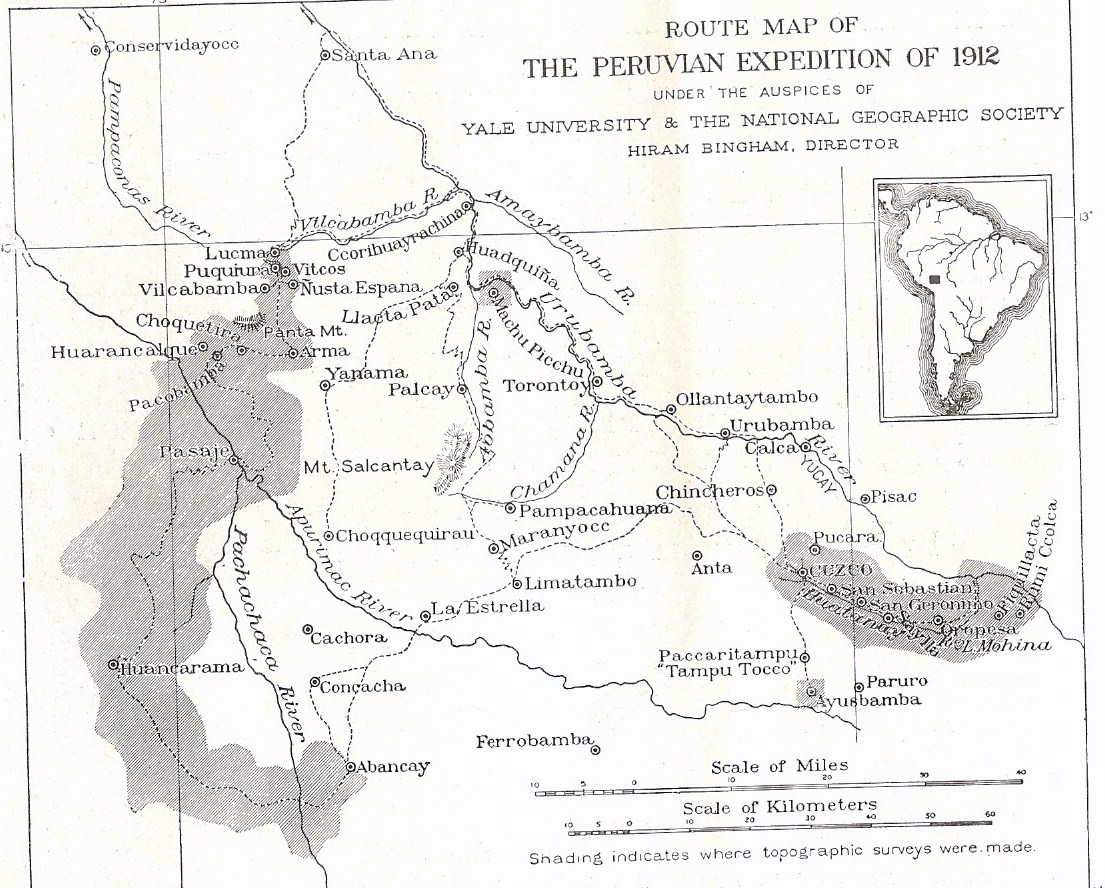

(Below: Hiram Bingham’s route (dotted line) in 1912; National Geographic, 1913)