Saving the Incas’ Mother Tongue, Quechua

posted on June 15th, 2008 in Incas, Indigenous Rights, Linguistics, Recent Discoveries

June 7, 2008

Armed With a Pen, and Ready to Save the Incas’ Mother Tongue

NYT

CALLAO, Peru

“Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago.”

Simple enough, right? But not for Demetrio Túpac Yupanqui.

Instead, he regales visitors to his home here in this gritty port city on Lima’s edge with his Quechua version of the opening words of “Don Quixote”:

“Huh k’iti, la Mancha llahta suyupin, mana yuyarina markapin, yaqa kay watakuna kama, huh axllasqa wiraqucha.”

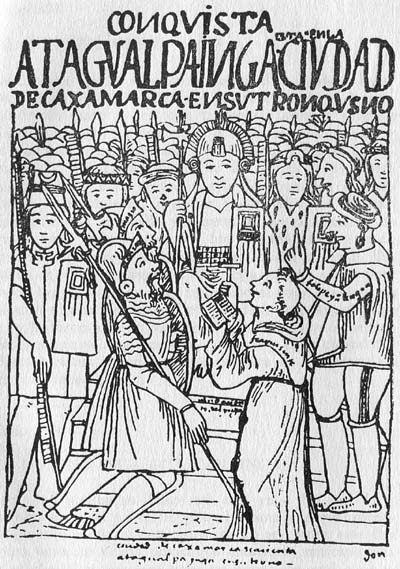

(Above: A 16th century drawing of Francisco Pizarro meeting the Inca emperor Atahualpa, in Cajamarca, Peru in 1532)

Mr. Túpac Yupanqui, theologian, professor, adviser to presidents and, now, at the sunset of his long life, a groundbreaking translator of Cervantes, greets the perplexed reactions to these words with a wide smile.

“When people communicate in Quechua, they glow,” said Mr. Túpac Yupanqui, who at 85 still appears before his pupils each day in a tailored dark suit. “It is a language that persists five centuries after the conquistadors arrived. We cannot let it die…”

Once the lingua franca of the Inca empire, Quechua has long been in decline. But thanks to Mr. Túpac Yupanqui and others, Quechua, which remains the most widely spoken indigenous language in the Americas, is winning some new respect.

Mr. Túpac Yupanqui’s elegant translation of a major portion of “Don Quixote” has been celebrated as a pioneering development for Quechua, which in many far-flung areas remains an oral language. While the Incas spoke Quechua, they had no written alphabet, leaving perplexed archaeologists to wonder how they managed to assemble and run an empire without writing.

Since the Spanish conquest, important writing in Quechua has emerged, but linguists and Quechua speakers hope that the new version of “Don Quixote” will be a step toward forming a public culture in the language, through Quechua magazines, television and books, that will keep its speakers engaged with the wider world.

After centuries of retreat in the Andes, Mr. Túpac Yupanqui’s efforts in fortifying Quechua, through teaching and translating, are being complemented by various other ventures.

Microsoft has released translations of its software in Quechua, recognizing the importance of five million or so speakers of the language in Peru and millions elsewhere in the Andes, mainly in Bolivia and Ecuador. Not to be outdone, Google has a version of its search engine in Quechua even if some linguists say that these projects were carried out more for corporate image polishing than for practical reasons.

The workings of Andean democracy are also reminding the world of Quechua’s importance. The government of President Evo Morales of Bolivia, for instance, is trying to make fluency in Quechua or another indigenous language mandatory in the civil service.

Here in Peru, two legislators from the highlands have begun using Quechua on the floor of congress. And President Alan García signed a law prohibiting discrimination based on language, even though its precise workings remain unclear.

These are small steps for a language threatened by the dominance of both Spanish and English amid Peru’s feverish link-up with the global economy following a bloody civil war in the last decades of the 20th century. Few people have toiled as long and hard as Mr. Túpac Yupanqui to give Quechua a fighting chance to survive a few centuries longer.

Mr. Túpac Yupanqui’s fascination with languages began in Cuzco, once the administrative center of the Incas, where he learned Latin and Greek as a young seminarian. He quickly seized on the importance of his native Quechua while traveling with priests to rural areas where they used the language in their sermons.

The son of a local politician, he was born in one of those highland villages, San Jerónimo, where Quechua surnames are common: Pachacútec, Sinchi Roca, Lloque Yupanqui and, of course, his own, Túpac Yupanqui, which is thought to illustrate lineage to Inca royalty. (Another esteemed Quechua name, that of Túpac Amaru, the Inca leader who led a 16th century rebellion against the Spanish, served as the inspiration for the name of Tupac Shakur, the rapper and actor who died in a drive-by shooting in 1996.)

Mr. Túpac Yupanqui might have remained in the highlands if not for a youthful philosophical quandary about Europeanized rational thought and spreading the word of God, which led him to abandon his clerical studies. “I simply decided that speaking about Descartes was not going to serve the Andean world,” he said.

So he moved to Lima and took up journalism. In the 1950s, he began writing a column for La Prensa, then an influential newspaper. He wrote often about the richness and subtleties of Quechua, a language long scorned by the light-skinned coastal elite.

Interest in his columns encouraged him to open Yachay Wasi, or “House of Learning,” an academy for studying Quechua, in the mid-1960s. The timing was propitious.

In 1968, a group of leftist military officers led by Gen. Juan Velasco Alvarado staged a coup. General Velasco’s government, an anomaly in an era when right-wing dictators ruled much of South America, promoted equal rights for indigenous groups and decreed Quechua to be on an equal legal footing with Spanish.

The classroom of Mr. Túpac Yupanqui, who was asked in 1975 to translate Peru’s national anthem into Quechua, bulged at the time with students from Peru and afar. He taught military officers, civil servants and a few foreign adventurers who took an interest in Peru’s indigenous peasants.

BUT three decades after the leftist generals made Quechua an official language, little linguistically is remembered by Spanish-speaking city folk about the Velasco years, which ended in 1975.

“A language cannot become official if a country is unprepared to train its schoolteachers to lecture in it,” said Mr. Túpac Yupanqui, who advised General Velasco on some of the policies. “No language is given life through something as fleeting as a decree.”

Mr. Túpac Yupanqui soldiered on after that earlier idealistic push for Quechua. After a stint in politics as spokesman for President Fernando Belaúnde Terry in the early 1980s, he returned to teaching Quechua at his one-room academy on the second floor of his home, where he still lives with some of his nine children.

He also continued making translations into Quechua, completing in 2006 his work on “Don Quixote,” a rare accomplishment in what has essentially been an oral language for more than a thousand years.

“The translation of Quixote is important not as a curiosity, but as a sign of what is to be done on a broader scale in the Andean republics if Quechua speakers are to be brought fully into their respective national communities,” said Bruce Mannheim, an anthropologist at the University of Michigan who specializes in Quechua.

Indeed, the intricacies of the translation were celebrated by linguists and literary critics alike, recognizing the challenges involved in translating the antiquated Spanish of Cervantes into a living language that, somewhat like Chinese or Arabic, has diverging dialects that can be mutually unintelligible.

Mr. Túpac Yupanqui’s eyes still light up when he discusses the grammar of Quechua (seven pronouns!) and what can be done to make it more resilient, like more radio projects and teaching it in schools alongside English.

“If Latin is said to be the language of the angels, then Quechua is the language for expressing the subtleties of existence on Earth,” he said. “That is why it is still alive.”

(Below: Mr. Túpac Yupanqui, theologian, professor, and Quechua Instructor)