The Last Days of the Incas’ Peru Tour #3 (Lima)

posted on May 23rd, 2008 in Incas, Lima, Peru, Peru, The Last Days of the Incas' Peru Tour

Lima (1 Day) The Plaza de Armas, Francisco Pizarro’s Statue, Pizarro’s Remains, Cerro San Cristóbal

The Strange Missing Skeleton of Francisco Pizarro

Although many tourists stay in Miraflores, one of Lima’s upscale and more modern suburbs on the coast, the most interesting area of Lima from a historical and visual point of view is its original center, built around the Plaza de Armas. Lima’s colonial downtown area, in fact, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988. This is the original square that Francisco Pizarro outlined in the barren sand in 1535, just a block south of the Rimac River, when he was 57 years old, and it was on this square (on its western side, across from the Cathedral) that Pizarro had his house built—and where he was later assassinated. The plaza is now fronted by the Palacio del Gobierno, on the same site where Pizarro built the first government palace; this is where the current Peruvian President lives.

On the eastern side of the square looms the cathedral, destroyed in a massive earthquake in 1746 and rebuilt on the same site during the following decade. In one of the apses of the cathedral lie Pizarro’s remains. In the distance (to the northeast) on the other side of the Rimac River, one can still see (and visit) the looming San Cristobal hill (Cerro San Cristóbal), where the Inca general Quispe and his army once camped during their assault on the fledgling capital, defended by Pizarro and roughly 100 of his desperate men…

The Cathedral with Francisco Pizarro’s remains (on the Plaza de Armas)

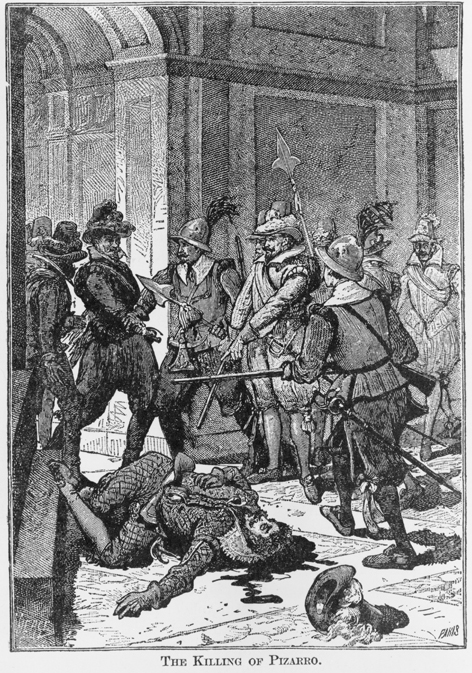

Followers of Francisco Pizarro’s one-time partner, Diego de Almagro, (whom Francisco’s brother Hernando killed), assassinated 63-year-old Francisco Pizarro on June 26, 1541, in his two story home, which once stood on the eastern side of the Plaza de Armas. Murdered with him were his half-brother, Francisco Martín de Alcántara and three others. After his assassination, some of Pizarro’s supporters quickly buried him behind the cathredral, afraid that his body would be dismembered or destroyed. Four years later, however, and despite the civil wars that now raged in Peru, Pizarro’s remains were reburied inside the cathedral in a crypt beneath the altar. In 1661, during a church inventory, church documents noted that officials had discovered a wooden sarcophagus, inside of which was a lead box. On the side of the lead box was inscribed in Spanish: “Here is the skull of the Marquis Don Francisco Pizarro who discovered and won Peru and placed it under the crown of Castile.” During the next two centuries, however, the location of that sarcophagus became lost.

In 1891, on the 350th anniversary of his assassination, the mummified remains of a man were discovered in the cathedral and were proclaimed to be those of the missing Pizarro. With great ceremony, the remains were placed in a bronze, marble, and glass coffin that was built for the occasion and were left for public display within the cathedral. For the next nearly ninety years, Limeños and other visitors paid their respects to the remains of the controversial conqueror, who had murdered an Inca emperor in order to rule and empire of his own. In 1977, however, a group of laborers working in the cathedral discovered a walled-over niche and within it a wooden sarcophagus and a small lead box. Within the lead box was a skull and on the side of the box was inscribed: “Here is the skull of the Marquis Don Francisco Pizarro who discovered and won Peru and placed it under the crown of Castile.” Inside the wooden sarcophagus they found the headless skeleton of an older, tall man inside, as well as the skeletons of two children and an elderly female. Were these the remains of Francisco Pizarro? And, if so, then whose mummy was on such an ostentatious display in the glass sarcophagus outside?

An investigative team consisting of a a Peruvian historian, an anthropologist, two radiologists, and two American anthropologists studied the remains. They quickly determined that the skull in the box with Pizarro’s name on it matched the headless skeleton and that the skeleton itself belonged to a man in his early sixties who had obviously been killed with multiple sword and dagger thrusts, thus matching the story of the rather brutal murder of Pizarro (forensic evidence detailed that, for example, a sword had pierced the man’s left eye, another had cut through the bone above the right eye, a knife had gone through the neck into the base of the skull, etc.).

The skeletons of the two children, it was presumed (and perhaps DNA testing could one day verify this), were those of Pizarro’s children, who had died young. The elderly woman’s skeleton, possibly, was that of his brother’s wife. Pizarro’s brother had died alongside him, after all, and his wife had helped to hide Pizarro’s body after he and her husband were slain.

As to who the individual was whose mummy had garnered nearly a century of lit candles and adulation in its specially made bronze, marble, and glass sarcophagus, the investigators had no idea. Perhaps it was a church official, it was thought. In any case, soon afterwards the mummy was “retired” and the “real” bones of Pizarro were placed in the same glass case. Thus, just inside Lima’s massive cathedral doors, in the quiet apse to the right, the curious can visit the macabre final resting place of Francisco Pizarro, the leader of a band of foreign ruffians who, more than four centuries ago, took control of the largest native empire ever to exist in the New World. And then destroyed both it and themselves.